Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Our man in Baghdad III.

[T]here's one thing that's becoming clear in the wake of the reprisal killings of Sunnis: The U.S. buffer isn't holding. Saleh Mutlaq, one of the most hardline Sunni political leaders, complained to The New York Times that "Sunni leaders felt betrayed that American soldiers did not stop the marauding Shiite militiamen on Wednesday." A member of a different, larger Sunni political faction--which for now has abandoned talks on the shape of the next government--bitterly told the paper the paper that "The security portfolio is in the hands of the Americans, but yesterday we didn't see any Humvees." According to the Times, the U.S. military is waiting for the next 48 hours to decide whether "a more visible American presence might be needed--in effect, sending American forces back into areas that they had turned over to the Iraqis." Mutlaq compares such relative inaction to the decision not to stop the looting that took place after the fall of Baghdad--with the clear implication that, now as then, the consequences will be disastrous, as Iraqis perceive the United States, during a moment of crisis, to be the worst of all things: an indifferent occupier.As far as I can tell from Ackerman, Khalilzad has

- "attempt[ed] to the curb the Shia death squads" (though the Shia see this as an effort to undercut them),

- tried to persuade Sunnis that the U.S. is not siding with the Shia and Kurds (but "the dynamic appears to have accelerated"), and

- "ask[ed] the Sunni and the Shia to think hard about whether they really want to descend into the abyss" (results: unclear, but not looking good).

eta: Wikipedia helpfully points to this profile of Khalilzad in The New Yorker, from last December.

Second cities.

Coming from Shanghai, Howard French visits Osaka and finds that "the scent of stagnation hangs unmistakably in the air." (Picture links to separate photo album.)

Monday, February 27, 2006

Why you would have to pay me to watch FOX News.

Rabies aside.

If you look, in fact, at emergency room statistics, you'll see that more people are admitted every year for non-dog bites than dog-bites -- which is to say that when you see a Pit Bull, you should worry as much about being bitten by the person holding the leash than the dog on the other end.I have no reason to question Gladwell's characterization of emergency-room statistics, but the second half of the sentence, though cute, certainly does not follow from the first.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

What we need now is another Cold War.

The Bush administration is quietly exploring ways of recalibrating U.S. policy toward Russia in the face of growing concerns about the Kremlin's crackdown on internal dissent and pressure tactics towards its neighbors, according to senior officials and others briefed on the discussions.Peter Baker, "Russian Relations Under Scrutiny," Washington Post A1 (Feb. 26, 2006).

Vice President Cheney has grown increasingly skeptical of Russian President Vladimir Putin and shown interest in toughening the administration's approach. ...

Cheney is "skeptical" of Putin now? I don't think so. He's been fighting the Cold War since he was a graduate student. And Putin's government has been suppressing dissent for years -- worrying about it now smacks of closing the barn door after the horses have hit the state line.

What I don't understand is whom Peter Baker thinks he's fooling. Anyone with a second-grade education can read the first two sentences of this article and understand that the Vice President's office cooperated with Baker, at the very least. So why does Peter Baker tell us that the Administration is "quietly" exploring its policy options? In my world, "quiet" government

action is the sort that isn't leaked to appear on the front page of the Sunday papers. This tells me is that Peter Baker is more interested in carrying water for his sources in the Administration than in telling his readers what is going on. A reason not to pay for the Post.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

Berlin.

Uranium fraud.

Icelandic ructions and the Brazilian real.

[I]n possibly the ultimate example of the butterfly effect, this weeks ructions in Reykjavik snowballed across the globe, setting off an avalanche of sell orders in emerging markets from Brazil to Indonesia.Steve Johnson, "Iceland in focus for wrong reasons," Financial Times 12 (Feb. 25-26, 2006).

The catalyst for chaos initially seemed to be country-specific. Fitch Ratings down-graded Iceland's debt, citing an "unsustainable" current account deficit, drawing parallels with the imbalances that helped trigger the 1997 Asian crisis.

The Icelandic krona promptly tumbled, losing 9.3 per cent of its value against the US dollar in a day-and-a-half as it slid to a 15-month low. Icelandic stocks and bonds also headed south.

But the icy blast spread as far as the tropics, and indeed every corner of the emerging market jungle, prompting the Brazilian real to fall 3 per cent, the South African rand more than 2 per cent, the Indonesian rupiah and Polish zloty 1.5 per cent and the Mexican peso and Turkish lire 1 per cent.

The contagion was primarily due to traders' need to liquidate profitable positions in order to fund their Icelandic losses.

Iceland's population is a shade under 297,000 -- more than 100,000 fewer people than live in East Baton Rouge Parish -- and yet because they have their own currency, the Icelandic government's management of its debt affects people from Poland to Indonesia.

Currency markets make for great metaphors: "snowballed . . . avalanche . . . icy blast . . . emerging market jungle . . . contagion."

Friday, February 24, 2006

Our man in Baghdad II.

Since Khalilzad's arrival in Iraq last year, he's been the best U.S. envoy conceivable, moving the United States beyond its alignment with the Shia and the Kurds and toward an engagement with Sunni factions that the United States had previously spurned as an undifferentiated enemy. And if Khalilzad couldn't heal sectarian divides--that's surely beyond the capability of any foreigner--he proved able to keep an incredibly precarious political process alive in the hope that its progress can ultimately alleviate sectarian distrust.So those are his goals. But what is he doing? A lot of cajoling. But we've already used buckets of carrots, and does anyone really fear the stick? Towards the end of the piece, we get a glimpse: "just this week he suggested an interruption of U.S. aid would result if the new government is too Shia-heavy." Maybe. Is there any reason to think he has President Bush on board that plan?

At any rate, the carnage this week suggests that all the talk about Khalilzad's diplomatic prowess have obscured facts on the ground:

For the last several months, the United States was so secure in the belief that the political process had secured Shia interests that it turned its attention to mollifying the Sunnis. The bombing and the outbreak of reprisal killings by Shia militiamen have shattered that assumption, and they risk turning Khalilzad's laudatory political strategy--that is, restraining the Shia in order to reach, at the least, a sectarian balance in governance--into a potential casualty of Samarra.So what, really, has he accomplished? It's still unclear to me, except that Khalilzad has managed to deeply impress the (relatively few) American journalists who are still trying to understand Iraqi politics. But perhaps they don't have a window into those politics that doesn't have Khalilzad next to it, explaining to them what they are seeing. The strategy may be laudatory, except when you consider where it's led us.

Not that the state of Iraq is Khalilzad's fault. Perhaps the whole enterprise was flawed from the start.

The Titanic, of course, was the most impressive passenger liner ever built. Had you stood next to the captain on the bridge as he steered through the North Atlantic, you might well have be impressed with his command of the ship, his knowledge of the sea, his authority over his crew, his concern for the well-being of his passengers, his skill and intelligence and manner. You might spend more time listening to him than looking out into the dark ahead of you.

Affirmative action's toll.

Annals of the law.

A small-town judge with three wives was ordered removed from the bench by the Utah Supreme Court on Friday. The court unanimously agreed with the findings of the state's Judicial Conduct Commission, which recommended the removal of Judge Walter Steed for violating the state's bigamy law.

Steed has served for 25 years on the Justice Court in the polygamist community of Hildale in southern Utah, where he ruled on misdemeanor crimes such as drunken driving and domestic violence cases.

The commission last year sought his removal from the bench after a 14-month investigation determined Steed was a polygamist and had violated Utah's bigamy law. Bigamy is a third-degree felony in Utah punishable by up to five years in prison and up to $5,000 in fines.

AP, via SFGate.

A fourteen-month investigation? That's almost five months per wife.

The cost of housing.

Landlords often want to find a way to force these tenants out, since their rent is below market rates:

"Essentially, it's a transfer of wealth," says Joe Bravo, a San Francisco attorney who represents both landlords and tenants. "The basic question is, Can the city impose on property owners to give up part of their wealth in order to accommodate seniors and disabled people? And my answer is, How else are you going to keep people who are old and disabled in the city?"The obvious answer that doesn't seem to have occurred to Bravo, and -- unfortunately -- cannot be found in Lloyd's column: The city could pay for it. These laws are designed to find a solution to a societal problem -- how to take care of the old and disabled -- without society having to share the costs. If San Francisco wants to keep old and disabled tenants in the city -- a great idea, if you ask me -- then it could give them money to pay market rates, or build city-owned housing for them. Instead, landlords get the bill. Actually, all San Franciscans end up paying more: everyone else pays more to rent or to buy because the housing shortage is exacerbated that much more, but those costs are hidden in other bills, meaning that the city government does not have to take the heat for passing the buck. This lets everyone blame landlords for being greedy -- so greedy that they would gladly evict a grandmother who "always pays her rent on time."

And then there are the tenants who are protected simply because they've been living in the same place for a while.

[O]ne tenant whose wife is protected and who also happens to have worked as a tenants' rights lawyer, argues that protected tenants laws shouldn't just be for society's most vulnerable groups. "It should be extended to any tenant who has been renting somewhere for five years," he says. "Housing is a basic human right."I agree that everyone should have a roof over their head, but this guy is talking about a right to pay the same rent in perpetuity. That's just loopy.

Warring tenants and landlords makes a great story, and many a San Francisco politician can sing from the tenants' hymnal. But if you think rents are too high, then you need to find a way to build more housing.

Is the greenish dead eye of your monitor staring at you?

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Furniture pron.

Reading vicariously.

If you would like to think about what it would be like to move to Montepulciano and get to know your rustic neighbors while eating all sorts of marvelous food, you could do worse than to pick up a copy of Ferenc Máté's The Hills of Tuscany: A New Life in an Old Land (Norton, 1988).

Over there.

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Summers' fall.

I have a soft spot for Larry Summers, who resigned yesterday as president of Harvard rather than face the humiliation of being fired. I admit that I develop a soft spot for almost everyone I spend 25 or 30 hours interviewing, as I did in Summers' case three years ago when I wrote a profile of him for the New York Times Magazine. I can't say that I found Summers' manner beguiling, or even prepossessing; he seemed, if anything, only barely socialized. But that's what I liked about him. Most university presidents are high-minded, silver-throated, and stupefyingly banal. Not Summers: The first time I heard him speak, when he was still Treasury secretary in the Clinton administration, he said something like, "There are two views on this subject, A and B, and I know I should say the truth lies between them. But it doesn't: A is right and B is wrong."(Here is my prior post re Summers.)

eta: Matt Yglesias explains some of the more substantive reasons Summers lost support among the faculty.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

Torture.

Speaking of Venice.

Probably the most amusing telegram of all time was by Robert Benchley, sent to his editor at The New Yorker after arriving in Venice for the first time: STREETS FULL OF WATER, PLEASE ADVISE.G. John Ikenberry, at TPM Cafe.

In February, though, I'd rather bare arms.

Our man in Baghdad.

Like others before him, David Ignatius praises Khalilzad as "a brilliant ringmaster of the Baghdad political circus." Khalilzad often gets this sort of praise, but for what? I can't recall anyone explaining what Khalilzad has achieved, except that he has done what U.S. journalists cannot or will not: learn who Iraqi's political leaders are and go talk to them.

eta: Khalilzad talks to the press, gets good marks from Kevin Drum.

Summers.

eta: Reuters says he will resign.

eata: Now he has resigned. Greg Anrig remembers a good deed. Otto remembers Andrei Schliefer (and if you don't know what he's talking about, click through -- it's remarkable). Brad DeLong reads his resignation letter.

The uses of precedent.

United States v. Martin, No. 04-6428, slip op. at 16 (6th Cir. 2006) (Martin, J., concurring). (The reference to Goldmember arguably is over the top.)[A]t oral argument counsel for the United States was asked if he could explain to the Court what types of offenses or common planning the government would concede to be related for the purposes of sentencing. Counsel had no idea. Instead, counsel spoke of such sophisticated planning that it believes is required under our case law that, in my opinion, only two types of criminals would be able to benefit from it: (1) perhaps a white collar criminal who keeps detailed records of the entire plan or (2) the James Bond movie villain, who prior to carrying out some grand scheme of world domination/annihilation, feels compelled to explain to anyone who will listen and in great detail (with intermittent villainous guffaws), each of the steps necessary to achieve his plan.[1]

____________

1 See also Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (New Line Cinema 1997).

DR. EVIL: Scott, I want you to meet Daddy’s nemesis, Austin Powers.

SCOTT EVIL: Why are you feeding him? Why don’t you just kill him?

DR. EVIL: In due time.

SCOTT EVIL: But what if he escapes? Why don’t you just shoot him? What are you waiting for?

DR. EVIL: I have a better idea. I’m going to put him in an easily-escapable situation involving an overly-elaborate and exotic death.

SCOTT EVIL: Why don’t you just shoot him now? Here, I’ll get a gun. We’ll just shoot him. Bang! Dead. Done.

DR. EVIL: One more peep out of you and you’re grounded. Let’s begin.

Prior to this exchange and then again following it, Dr. Evil describes in great detail the separate crimes necessary to achieve his plan for world domination. Thus, if our Government ever does find Dr. Evil (or chooses to prosecute him despite his recent decision to be "less evil," see Austin Powers in Goldmember (New Line Cinema 2002)), he will be one of the few, if any, criminal defendants, able to argue, consistent with this Circuit’s precedent, that all of his various crimes were "related" for purposes of the Guidelines.

Cittadini Non Distratti.

The private citizens solve two problems faced by traditional law enforcement: The pickpockets can recognize the police fairly easily, and out-of-town tourists do not stick around to testify.

It strikes me that this sort of vigilantism would not work so well in the United States because of guns. Rightly or wrongly, I suspect that the citizens who would volunteer would be inclined to carry guns, which would cause problems. The notion that pickpockets or the citizens apprehending them might be armed and violent does not even seem to occur to anyone in Venice (or at least to Slate's writer there).

Censorship in the age of e-mail.

Monday, February 20, 2006

One-stop shopping.

Sunday, February 19, 2006

Hi, Hank.

A fox sees a hedgehog trying to multitask?

POTUS and Veep.

They are still figuring out this new-fangled interwebs thing.

Paving a road to Hell.

Saturday, February 18, 2006

Blogging considered, 2.0.

I would have expected more blogospheric reaction to the big Financial Times article about blogging today -- maybe I'm not looking under the right rocks. It strikes me as a fairly stale rehash of blogs from a journalistic perspective, and a chance missed to consider what is new and different about blogs as a tool. (That would be an opportunity cost.) This article surely captures Trevor Butterworth's interest in blogs (or lack thereof, although he seems to have been on the net for a while): "[B]logging would have been little more than a recipe for even more internet tedium if it had not been seized upon in the US as a direct threat to the mainstream media and the conventions by which they control news." At least one mainstream journalist is heading to the ramparts to defend his turf from the likes of Hugh Hewitt, although Butterworth describes him as a "syndicated radio host and law professor" who has written in the Weekly Standard, apparently oblivious to the fact that he also blogs. Thus, while noting that new blogs start every minute, Butterworth is uninterested in what these bloggers are doing. His preoccupation is those few blogs most like newspapers in their ability to claim a substantial readership.

And how better to put them in their place than quoting a few outrageous claims for blogs? Then all you need is someone who's left a blog to find a place with a newspaper, like, say, Gawker veteran and senior editor at the New York Observer Choire Sicha:

“The word blogosphere has no meaning,” he said from across a folding table vast enough to support the battle of Waterloo in miniature (the apartment owes much to eBay, the Ikea of bohemia). “There is no sphere; these people aren’t connected; they don’t have anything to do with each other.” The democratic promise of blogs, he explained, has just produced more fragmentation and segregation at a time when seeing the totality of things - the purview of old media - is arguably much more important.The delight that Butterworth (and his editors?) find in this diagnosis is almost palpable.

“As for blogs taking over big media in the next five years? Fine, sure,” he added. “But where are the beginnings of that? Where is the reporting? Where is the reliability? The rah-rah blogosphere crowd are apparently ready to live in a world without war reporting, without investigative reporting, without nearly any of the things we depend on newspapers for. The world of blogs is like an entire newspaper composed of op-eds and letters and wire service feeds. And they’re all excited about the global reach of blogs? Right, tell it to China.”

And they back it up with some facts about blogging economics that will be familiar to anyone who has put down a newspaper long enough to spend some time on-line. Turns out there's not a lot of money in blogs. (Who knew?) So they can't afford to hire many people (read: no jobs for journalists) and they're not making much in advertising, whcih means "advertisers are still sticking with the mainstream media" (read: our jobs are safe).

For a moment, the whiff of something new and interesting breezes into the room:

“There is a certain loss of control when it comes to advertising on blogs,” said Mark Wnek, chairman and chief creative officer of Lowe New York. “The connection the most popular citizen journalists cultivate with their devotees is through an honest, uncensored, raw freedom of expression, and that can be quite uncomfortable territory for a traditional marketer.”Sounds interesting, no? Not to Butterworth, who is more focused on where those traditional marketers are spending their money than on what might be said with an honest, uncensored, raw freedom of expression. And "raw," it turns out, reassures Butterworth that people who can write solid, journalistic sentences will always be in demand. Trailing that whiff of the new thing is what one might call a cloud of dubious orthodoxy.

Although Butterworth's article runs to great length by print standards, there is little hint in his article that he has much idea of what bloggers actually are doing with this new technology even as they fail to displace the mainstream news media:

[I]n the end, . . . the dismal fate of blogging" is that "it renders the word even more evanescent than journalism; yoked, as bloggers are, to the unending cycle of news and the need to post four or five times a day, five days a week, 50 weeks of the year, blogging is the closest literary culture has come to instant obsolescence. No Modern Library edition of the great polemicists of the blogosphere to yellow on the shelf; nothing but a virtual tomb for a billion posts - a choric song of the word-weary bloggers, forlorn mariners forever posting on the slumberless seas of news.Something new and different is going out here on the interweb, but if Trevor Butterworth has something to say about it, you wouldn't know from this article. (Though you could tell him.)

Instead of writing about what blogs are not doing, the Financial Times could have chronicled what they are up to. To take an example of particular salience to traditional journalists, blogs provide a tool to open up what you might call "an illiberal press, which works to restrict the free market of ideas." Take the example of Deborah Howell, the Washington Post ombudsman. (Take her, please!) She touched off an internet "firestorm" by writing that Jack Abramoff gave money to both parties, and then stuck to her guns, continuing to paint Abramoff as corrupt in a bipartisan way. A couple of years ago, might have prompted a couple of angry letters to the editor, of which the Post might have run one or two. Not now. Blogs fueled the outrage, both by permitting Howell's critics to self-publish, but also by giving the Washington Post's readers the conviction that they are not simply passive consumers of whatever the Post might deign to tell them, but participants in a dialectic process. Indeed, the Post itself buys into this bold new world, not just with its web site, but also with a blog that invites reader comment. Or invited -- faced with the reaction to Howell's work, the editors shuttered the blog, and only just re-opened it.

Even if the blogs that criticized the Post in this episode are not about to supplant its reporting or plunder its advertisers, there is a new dynamic here that Butterworth fruitfully might have explored. For example, exploring the Post's side of the story might have been interesting. Bloggers have failed to get answers to many of their questions for the Post, but maybe the Post's editors would have felt compelled to answer a reporter from the Financial Times. More broadly, the Howell episode is a small window onto the many ways in which Washington journalism lately has been exposed -- by bloggers -- as hidebound: the dependence on official sources, often unattributed; the compulsion to tell two sides of every store; the unwillingness to contradict public figures who say ridiculous things; the willingness to be played and spun; the preference for covering the game of politics rather than matters of policy; and so on.

The Deborah Howell saga sits at the borders of the corner of the blogosphere which Butterworth actually discussed -- bloggers who focus on the news. But that's like dismissing the telephone because people will always have clocks. Technorati says that Boing Boing is more popular than any of the sites mentioned by Butterworth, and it offers something distinct from traditional media. For academics, sites like Crooked Timber, The Volokh Conspiracy and Cliopatria offer a way to circulate and develop ideas without publishing them in the traditional journals. Many people uses blogs as journals, which you can read to keep up with people you know or people you don't. I could go on and on -- that's just scratching the surface.

While none of these threaten the Financial Times's market share or Trevor Butterworth's professional standing, I imagine that if he gave some serious attention to them, or the many other things happening out there that I don't even know about, he might have something interesting to say about them.

eta: As you may have gleaned from one of the links above, Butterworth started a blog for the discussion of the piece, and has been responding to readers who post on it. I posted a link to this post, and a rather lengthy follow-up post as well. (Butterworth is moderating the comments, and my second post hasn't yet appeared as I write, though I'm sure it will.) The whole thread is worth a look. Now that I've read that exchange, I take the spirit of the original piece somewhat differently, and would not have written in the same tone.

eata: Jack Balkin hits many of the same topics here.

Quick pivot.

Friday, February 17, 2006

This is your GOP.

Congressmen are hanging out in K Street warrens like addicts in 19th century opium dens, but instead of Chinese dudes passing out pipes, there are lobbyists handing out checks, golf trips and other prizes from behind Curtain No. 2 on "Let's Make a Deal." The Contract With America that brought the Republicans to power more than 10 years ago is a distant blur in the GOP's rearview mirror. Smaller, competent and restrained government has been sacrificed to the new coalition of Republican rent-seekers.OK.

Compassionate conservatism may have had some intellectual rigor when it was the stuff of egghead journals and think tank conferences, but under Bush it has always been a marketing strategy designed to justify spending vast sums of money. This shattering of the GOP's at-least nominal commitment to limited government has not only resulted in a bidding war between Congress and the White House on how "best" to expand government, it has also caused philosophical incontinence on the right.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

New.

Odd cuisine.

50 U.S.C. s 1811.

Over at Captain's Quarters today, it is open season on George Will for failing to toe the President's line. Will writes

that warrantless surveillance by the National Security Agency targeting American citizens on American soil . . . violates the clear language of the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which was written to regulate wartime surveillance.Perhaps not the most felicitous phrasing, since FISA had other goals, too. Hard to argue with, though, and the Bush Administration isn't even trying -- as a statutory matter, they're saying that FISA was amended by the Authorization for the Use of Military Force in Afghanistan, a whole 'nother can of worms.

But Captain Ed is willing to try to push the envelope to defend the White House:

This is patently untrue. FISA came into being to regulate peacetime surveillance by the federal government, as an antidote to Nixonian abuses of power that had nothing to do with the conduct of war. . . .Um, no. That's just wrong. Let's look at FISA. It's an unpleasant acronym, but unlike the facts about what the NSA may or may not be doing, what it says is actually something that you can consult and learn. And, hey, it turns out that part of FISA specifically was drafted to govern electronic surveillance during wartime:

The authority to conduct wartime surveillance on one's enemy, regardless of whether one terminus of the communication was located in the US, has never been questioned until now.

Notwithstanding any other law, the President, through the Attorney General, may authorize electronic surveillance without a court order under this subchapter to acquire foreign intelligence information for a period not to exceed fifteen calendar days following a declaration of war by the Congress.

50 U.S.C. s 1811. And as Will implied, this provision dates from 1978.

So let's see if Ed is willing to acknowledge that he, not George Will, got it wrong.

More on the AUMF and FISA here (in short: read the AUMF and FISA). Why Ed is wrong when he suggests that Congress has no role in how wars are conducted here (in short: read the Constitution).

Update: A full day since I posted this, and while the Captain has updated his post twice, he hasn't acknowledged or corrected his error. What can you do?

Another Update: Now he's acknowledged the mistake. Apparently you have to have Glenn Greenwald's page hits to get his attention.

Worth every penny of its price.

"What scares me is the consumer who goes out there and makes a decision based on that data," said Richard Powers, president of the Appraisal Institute, the nation's largest appraiser association with 21,000 members. "Consumers really have no way to judge the accuracy of the estimate -- that really is the problem."For that matter, Zillow's own data suggests they're not doing well:

Powers said his board members have had mixed results on tests they've been running since Zillow's public beta test went live. "In some areas, we found the results were fairly accurate to the value of the home. In others, we found results that were at least 40 percent wrong."

Zillow runs extensive analyses to calculate its own accuracy rate by comparing actual transactions as they occur with the automated estimates provided by its computerized valuation system. Nationwide, 62 percent of all Zestimates fall within 10 percent of the selling price, according to Zillow. That means 38 percent are more than 10 percent off the mark, which strikes me as significant.Hell, even 5-10% is significant when you're in the market.

Zillow has potential. It would be nice if they could make it work.

"This faux toughness is folly."

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Toon blogging.

Domestic-spying polling.

Wrong 50%

Right 47%

No opinion 3%

CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll, Feb. 9-12, 2006.

More cartoons that might offend in the Middle East.

I miss Polly Esther.

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Good books cheap!

Surf's up.

- Pretty harsh words from Ann Althouse for Dick Cheney.

- Not Altmouse, though I see the confusion.

- Dick Cheney and The Most Dangerous Game.

- Joel Stein doesn't support the troops.

- Eric Weiner on domestic wiretapping in Europe.

- In a reversal of past policy, the U.S. votes with Iran, Cuba and Zimbabwe to deny UN consultative status to gay and lesbian groups.

- Glenn Greenwald on Glenn Reynolds & Ann Coulter.

- Jane Galt on the budget.

- Happy Valentine's Day.

Seeing orange.

The White House has decided that the best way to deal with Vice President Dick Cheney's shooting accident is to joke about it. President Bush's spokesman quipped Tuesday that the burnt orange school colors of the University of Texas championship football team that was visiting the White House shouldn't be confused for hunter's safety wear.AP story and graphic via TPM.

"The orange that they're wearing is not because they're concerned that the vice president may be there," joked White House press secretary Scott McClellan, following the lead of late-night television comedians. "That's why I'm wearing it."

Article II and FISA.

I.e., if FISA does purport to limit this power, it is unconstitutional.Article II of the Constitution makes the president commander in chief of the armed forces. If this clause means anything, it means that the president (and not Congress) directs military operations. . . .

When prosecuting wars, the president acts as commander in chief. Congress cannot diminish this authority, any more than it can make it a crime for him to veto a bill or pass laws requiring him to pardon convicted terrorists.

The fundamental question here concerns the scope of the President's powers as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States” -- what those powers entail. (Famously and analogously, the First Amendment protects “the freedom of speech,” but not permit one to yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater – the hard questions are what that freedom of speech encompasses.)

Virginia Patriot’s approach to this question is a functional one. Intelligence gathering is an inherently military function:

For starters, I submit that VP’s argument fails on its own terms. No one (that I know of) has suggested that the military needs to obtain FISA warrants before it engages in aerial reconnaissance or intercepts enemy radio traffic. Those look and smell like traditional military activities. But listening in on telephone calls made by American citizens? I can imagine D-Day without them. And it's not the armed forces who are tapping phone lines.Military campaigns and intelligence gathering go hand in hand; they are often indistinguishable. (Imagine D-Day without aerial reconnaissance or intercepts of German radio traffic!)

Most intelligence comes from human or electronic snooping abroad. What if the enemy threatens America? An enemy submarine - an intelligence gold mine - slips into New York harbor. May Congress, having authorized force, now require a warrant before (or after) the Navy intercepts the sub's communications, seizes the vessel or searches it for code books or other intelligence? Such overreaching would improperly strain the president's power, as commander in chief, to direct military operations. Congress, too, must follow the Constitution.Presidential powers do not evaporate if U.S. residents aid the enemy. What if an American radios our hypothetical submarine? May Congress require the commander in chief to satisfy a court before listening? Hardly.

Nor must the president seek approval before monitoring communications between al-Qaida and suspected accomplices. A warrant-based "cops and robbers" approach is wholly out of place in time of war. FISA's backwards-looking civilian law enforcement model would hamper the president's ability to identify targets of pre-emptive action before they strike and undermine his ability to fight the war Congress authorized.

But, respectfully, Virginia Patriot is asking the wrong question, too. Here we have an argument about a constitutional provision dating from 1789, and the answer is to be found in hypothetical situations from World War II? Arguing that the Constitution should be construed so as to accommodate whatever policy needs seem most pressing -- let's just say that Edmund Burke is spinning in Beaconsfield Church.

Under Virginia Patriot’s approach to Article II, how are we to determine the scope of the President’s powers as commander in chief? For all the talk of enemy submarines and D-Day, the argument is that we are in a new kind of war, one that -- VP suggests -- might be confused for law enforcement. Virginia Patriot’s argument prompts the question: Are there any limits to the constitutional power that he is describing? I can think of a great many things that a president might feel a need to do in the name of national security, such as torture, emprisonment, seizure of property. The logic of the functionalist approach encompasses all these things, and more, on the commander in chief's ipse dixit.

Perhaps you think this is good policy. I don’t. But reasonable people will often disagree about policy. We have a constitution and theories of interpretation to try to keep constitutional debates from becoming policy debates.

Consider, then, an originalist principle. The Constitution was drafted with the lessons learned from the War of Independence, in which we revolted against King George III, a monarch whose power was hardly checked by Parliament. From these origins we trace a fundamental principle with which it is hard to square a unfettered Article II commander in chief, that of the separation of powers. As even the President’s defenders acknowledge, his assertion of power under Article II is a demand that we trust him with unchecked power. This is antithetical to our constitutional tradition, and it is anything but conservative.

We don't need to think ill of the President to think it's a bad idea to trust him (although you might think that the possibility that Hillary Clinton will be the next President would be enough to scare conservatives here). Consider this, from a recent profile of Bush aide Michael Gerson:

When I asked Gerson about the recent domestic-spying controversy, he replied, almost irritably, “These are the appropriate constitutional and necessary methods to defend American liberty.” He added, “The President views us as at war, and he’d much rather be on that side of things than have to apologize after an attack. I don’t want to write any more ‘days of national mourning’ speeches.”

I would expect this or any President to balance national-security needs and civil liberties in this way, but that does not make it the right balance. As Gerson's response suggests, the President will be more sensitive to some threats than others. Gerson is not going to write a speech mourning the loss of civil liberties. And a second-term President will not face the voters again, insulating him from a need to worry about what the public might think.

The Constitution not only has principles in it -- it has a text, too, and there's quite a bit there that informs this debate. For example, the Second, Third and Fourth Amendments tell us something about the founders’ concerns about the relationship between the citizens and their army. As good conservatives know, the Second Amendment embodies a concern that the standing army be checked by well-regulated militia. The Third Amendment reflects a desire to protect citizens’ houses from troops, in the most immediate and literal way. As does the Fourth Amendment, in a different manner. On its own, the Fourth Amendment reflects more of a concern with impeding the federal government’s gathering of information than any constitutional provision does in furthering it.

More to the point is Article I, which gives various powers to Congress. Lo and behold, many of them circumscribe the broad powers the President's friends are claiming for him under Article II:

The Congress shall have Power To . . . provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States;Article I, Section 8.

To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water;

To raise and support Armies, but no Appropriation of Money to that Use shall be for a longer Term that two Years;

To provide and maintain a Navy;

To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces;

To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States . . .;

* * * * *

To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Reading these provisions, I do not understand the claim that Congress has no business enacting FISA. If the President is the commander in chief, nevertheless it is Congress’s role “[t]o make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval forces.” Such rules must necessarily constrain the CIC’s discretion, and yet that is the constitutional scheme. Indeed, but not for congressional action, there would be no military at all, for it falls to Congress, not the President, “[t]o raise and support Armies” and “[t]o provide and maintain a Navy.” As I understand the Constitution, Congress simply could decline to fund the NSA, or those of its activities which are now at issue. Congress, not the President, appropriates the moneys that pay for domestic spying.

In fact, re-consider that most absurd-sounding hypothetical:

An enemy submarine - an intelligence gold mine - slips into New York harbor. May Congress, having authorized force, now require a warrant before (or after) the Navy intercepts the sub's communications, seizes the vessel or searches it for code books or other intelligence? Such overreaching would improperly restrain the president's power, as commander in chief, to direct military operations.Actually, the Constitution says otherwise. It gives Congress the power to "make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water."

Now, one can argue about whether provisions like this one, originally drafted in the context of eighteenth-century privateering, should be changed to fit the conflicts of the twenty-first century. If the President thinks that the Constitution, or FISA, needs to be revised for a new day, then that is the conversation we should be having.

Monday, February 13, 2006

And I'm agreeing with him even if it offends you.

Some of the commentary on the cartoons in the farther reaches of the internet has that quality to it --of a desire to throw off the subterfuge and get on with the "clash of civilizations." . . . .Publishing material that will offend Moslims just for the sake of 'showing them that we won't be intimidated' is playing into the hands of the radical Islamists who are stirring the pot and benefiting from this uprest. There's a battle in the Islamic world between radicals and moderates. If we're going to start enlisting the press, we might as well do a little thinking about whom we're trying to help. Though I still think that turning the other cheek is the better way to show that we can't be intimidated.

Defending the right to publish offensive material . . . mean and shouldn't mean having to defend the content published. And it certainly doesn't mean having to reproduce the material. . . .

Some are arguing that the cartoon with Mohammed wearing a bomb isn't offensive, a very different argument from the "cartoons are offensive, but the West defends the right to be offensive." Would a cartoon of Christ's crown of thorns transformed into sticks of TNT after an abortion clinic bombing be offensive? Of course it would be . . . . At least begin with the obvious: Some of the cartoons were offensive.

. . . [M]ost of the commentary on the cartoons seems to me to be off point. I have yet to see any commentator --in the U.S. at least-- who is demanding the Danish government apologize or that press freedom be restricted in any way. I haven't seen any commentator argue that threats aginst the papers that published the cartoons are other than evil, or that the burning of embassies or other manifestations of jihadist rage are anything but condemnable.

But the central issue is largely unaddressed: Does the press in the West owe the war effort against the jihadists nothing, or even anything at all? The jihadists are hungry for information and for propaganda. If the West's media is eager to supply either or both, there isn't much anyone can do to stop that supply -- nor should there be -- except via careful reminders to responsible journalists that there's a war on, and everything that is printed is part of that war.

Some of my e-mail is full of the predictable "We are already at war with Islam" nonsense. We aren't, and we should do everything in our power to prevent such a catastrophe. From Soxblog:Many commentators want to define the debate as an either/or choice between the cartoonists and the jihadists. That's not the debate at all, and suggests an inability to grasp the real complexity here. It is not only consistent but compelling to both demand that the jihadists who threaten the press or who burn embassies be defeated and to also conclude that the cartoon fiasco was an unnecessary and expensive diversion from the central confrontation with the jihadists.I believe that the vast majority of people, regardless of what faith they are born into, will opt for peace and prosperity over war and hardship if they have such a choice available to them. The argument that Muslims are inherently different from all other peoples in this regard is fatuous in the extreme. Examples of hundreds of millions of Muslims who have chosen a lifestyle that doesn't feature violent Jihad is easily attainable.

None of this makes their dangerous co-religionists any more cuddly or less threatening. The menace posed by the Jihadist mentality is undeniable. Calling it out and identifying it is a necessary precursor to fighting it.

But demonizing a billion people because of the faith they were born into is not.

Or, as Fontana Labs says:

You might not believe this, but my high-level, super-secret contacts in the Muslim world have intimated that there's actually a trace element of dissent in the Umma about this: apparently some Muslims are not actually in favor of rioting over cartoons. It's very hard to spot, because in other ways Muslims are completely homogenous-- but there might be one or two we could spare from either internment or deportation.

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Yoo too?

Faithful George? Not so much.

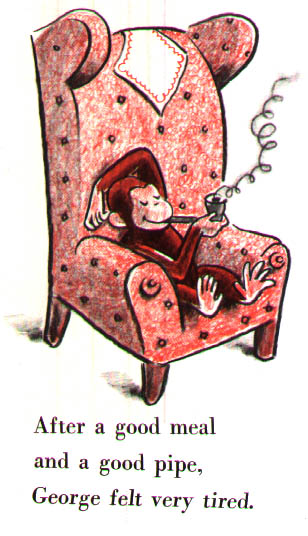

Reviewing the new Curious George movie, the San Francisco Chronicle's Pop Culture Critic Peter Hartlaub writes:

Count me among the moviegoers who would be completely happy only with a George movie that gets the Frank Miller/"Sin City" treatment -- adapting H.A. and Margret Rey's seven books with a near-maniacal frame-by-frame faithfulness to the source material.Hartlaub ought to take another look at the books. Aesthetically, the movie will be familiar to anyone who knows the books, for a variety of reasons that Hartlaub goes on to discuss. But the books' moral content is gone.

The "Curious George" feature film . . . makes only casual references to the books. But despite the modernization of the monkey who gets into mischief -- including a picture cell phone that becomes central to the plot -- George Version 2.0 isn't sacrilege, either. It's an entertaining movie for kids, which pays enough tribute to the original authors that "George" purists should forgive all but one or two of its transgressions.

In the books, because George is a monkey, he can get away from his parent figure, the Man in the Yellow Hat. George goes off on his own, and he misbehaves, as monkeys are wont to do. But he also gets the opportunity when he's off on his own to do something good, without anyone asking, and he does. Before the story ends, he returns to The Man in the Yellow Hat, and there is always a reckoning. George is admonished for his bad decisions and congratulated for his good ones.

In the movie, the plot's focus, and the moral focus, are Will Ferrell's Man in the Yellow Hat. Curious George has no voice; he is an object of our attention and affection, but he's no subject. He misbehaves, but there are never any consquences, because he's cute. And The Man in the Yellow Hat misbehaves, too, but there are never any consequences for him, either. He's a grown man, but he can take balloons from children at the zoo, and the movie's plot revolves around a miscommunication he fails to correct. We all worry that it will work out, but we never have to worry that he will do the right thing -- the old moral compass is nowhere to be found, and such fusty questions apparently are no longer entertained, or entertaining.

The movie is fine for what it is, but let's not pretend it's old-skool.

Young capitalists, on the road.

The news was bad: the dollar was quoted at fifty Afghanis, but the first shock the hippies got was from a sleek robed man who beckoned to a chief and offered him forty-five Afghanis.Paul Theroux, "Memories of Old Afghanistan," Sunrise with Seamonsters: Travels & Discoveries, 1964-1984 115-16 (Houghton Mifflin, 1985).

"So the black market rate is lower than the bank's. Right? Beautiful."

"I remember when you could get seventy to the dollar."

"Seventy! I remember when it was around ninety -- and a bed was fifteen. You figure it out."

They stood in groups, cawing like brokers faced with a plunging market, the worst in years. And the amazing thing was that these youths, whose own description of themselves was "freaks" -- the girl in the torn blouse, the bearded one with the cracked guitar, the boy who walked around in his bare feet during that very cold night in no-man's land, the ones in pajamas, pantaloons, dhotis; the men with ponytails, skullcaps, and sombreros, the girls with crew cuts and copies of Idries Shah, all of them fatigued after their flight across Turkey and Iran -- the amazing thing, as I say, was that they talked with impressive caution about money. They were carrying French and Swiss francs, German marks, sterling and dollars; their money was in greasy canvas pouches and gaily colored purses and sequined bags with drawstrings.

At times, when the topic was drugs or religion, they were impossible to talk to. They struggled with the debased language of drug psychosis to express abstract concepts they had got third-hand from drop-out philosophy majors. But when the subject was money, they never mocked: they were serious, cunning and shrewd by turns, because they knew -- even better than their detractors -- how much their life, so seemingly frivolous, was underpinned by cash.

Saturday, February 11, 2006

Statutory cover.

Via Mort Halperin and Laura Rozin, whom I assume have quoted the transcript correctly. Gonzales has to keep insisting that FISA does not say what it clearly says, because it is the only defense for what he said during his confirmation hearings.SEN. FEINGOLD: I — Judge Gonzales, let me ask a broader question. I’m asking you whether in general the president has the constitutional authority, does he at least in theory have the authority to authorize violations of the criminal law under duly enacted statutes simply because he’s commander in chief? Does he — does he have that power?

...

MR. GONZALES: Senator, this president is not — I — it is not the policy or the agenda of this president to authorize actions that would be in contravention of our criminal statutes.

Stirring up cartoon rage.

As leaders of the world's 57 Muslim nations gathered for a summit meeting in Mecca in December, issues like religious extremism dominated the official agenda. But much of the talk in the hallways was of a wholly different issue: Danish cartoons satirizing the Prophet Muhammad.(Also see the account from Kos linked in the first bullet point here.)

The closing communiqué took note of the issue when it expressed "concern at rising hatred against Islam and Muslims and condemned the recent incident of desecration of the image of the Holy Prophet Muhammad in the media of certain countries" as well as over "using the freedom of expression as a pretext to defame religions."

The meeting in Mecca, a Saudi city from which non-Muslims are barred, drew minimal international press coverage even though such leaders as President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran were in attendance. But on the road from quiet outrage in a small Muslim community in northern Europe to a set of international brush fires, the summit meeting of the Organization of the Islamic Conference — and the role its member governments played in the outrage — was something of a turning point.

After that meeting, anger at the Danish caricatures, especially at an official government level, became more public. In some countries, like Syria and Iran, that meant heavy press coverage in official news media and virtual government approval of demonstrations that ended with Danish embassies in flames.

In recent days, some governments in Muslim countries have tried to calm the rage, worried by the increasing level of violence and deaths in some cases.

But the pressure began building as early as October, when Danish Islamists were lobbying Arab ambassadors and Arab ambassadors lobbied Arab governments.

"It was no big deal until the Islamic conference when the O.I.C. took a stance against it," said Muhammad el-Sayed Said, deputy director of the Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo.

Sari Hanafi, an associate professor at the American University in Beirut, said that for Arab governments resentful of the Western push for democracy, the protests presented an opportunity to undercut the appeal of the West to Arab citizens. The freedom pushed by the West, they seemed to say, brought with it disrespect for Islam.

He said the demonstrations "started as a visceral reaction — of course they were offended — and then you had regimes taking advantage saying, 'Look, this is the democracy they're talking about.' "

The protests also allowed governments to outflank a growing challenge from Islamic opposition movements by defending Islam.

FISA and the AUMF.

(I note parenthetically that a lot of conservative blogs suggest that the NSA is looking only at international communications with members of Al Qaeda, while a lot of lefty blogs suggest that the Administration is poking through all manner of domestic communications. My understanding is somewhere in the middle. If I've got it correctly, the Administration is following up on leads suggested by, e.g., information connected abroad, and in doing so may be intercepting communications involving U.S. residents and citizens who are a few degrees of separation away from anyone in Al Qaeda. I would appreciate pointers to materials that try to clarify this question. In any event, I will assume that FISA forbids whatever the NSA is doing.)

VP first argues that as a matter of statutory interpretation, the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force against the Taliban and Al Qaeda, Pub. L. No. 107-40, 115 Stat. 224 (2001) ("AUMF") trumps FISA:

[A] Sept. 14, 2001, congressional resolution recognized the president's "authority under the Constitution to take action to deter and prevent acts of international terrorism against the United States." The resolution also empowered him to "use all necessary and appropriate force" against "nations, organizations or persons" that "he determines planned, authorized, or aided the September 11 attacks."The first sentence doesn't help on the statutory argument, since merely "recognizing the president's authority" does not purport to change the balance between the executive and legislative branches' authorities struck in FISA. So the question is whether the AUMF's reference to "all necessary and appropriate force" amended FISA, if you will.

Many in Congress who voted for the AUMF say they never intended as much, and I have yet to see any legislative history or contemporary accounts suggesting that legislators actually contemplated what VP and others are now arguing. More to the point, then-Senator Daschle has said that the White House proposed a revision to the text of the AUMF that would have expressly referred to domestic powers:

Literally minutes before the Senate cast its vote, the administration sought to add the words "in the United States and" after "appropriate force" in the agreed-upon text. This last-minute change would have given the president broad authority to exercise expansive powers not just overseas -- where we all understood he wanted authority to act -- but right here in the United States, potentially against American citizens.That this revision was not made suggests, again, that Congress did not understand itself to be limiting FISA in the way VP now suggests.

The heart of Virginia Patriot's argument -- both constitutional and statutory, if I'm reading him correctly -- is that electronic surveillance of the sort in which the NSA is engaged is at the heart of the sort of use of force envisioned by the AUMF and implicated by Article II. With regard to the AUMF and FISA, I think you can assume that this is true and still conclude that the AUMF did not alter FISA's scheme. (I'll return to the Article II perspective.) The problem for VP is that FISA specifically permits warrantless wartime domestic electronic surveillance, but only for the first fifteen days of a war. 50 U.S.C. § 1811. This provision gives the Executive Branch some latitude in the first days of a conflict, but only in those first days.

Since FISA's scheme explicitly addresses wartime intelligence-gathering, it's very hard for me to understand how Congress could be said to have amended FISA implicitly by granting the President wartime powers. Had Congress declared war on Afghanistan and Al Qaeda, it would be unreasonable to construe that declaration as altering FISA, and Virginia Patriot describes the AUMF as "having authorized war." The suggestion that intelligence-gathering is an integral part of warmaking only tends to confirm that the AUMF and FISA are complementary.

A slightly different way of putting this, in accord with a traditional principle of statutory construction, is that FISA specifically addresses wiretapping during wartime, and the AUMF does not. As better minds than I put it:

[The] argument rests on an unstated general "implication" from the AUMF that directly contradicts express and specific language in FISA. Specific and "carefully drawn" statutes prevail over general statutes where there is a conflict. Morales v. TWA, Inc., 504 U.S. 374, 384-85 (1992) (quoting International Paper Co. v. Ouelette, 479 U.S. 481, 494 (1987)). In FISA, Congress has directly and specifically spoken on the question of domestic warrantless wiretapping, including during wartime, and it could not have spoken more clearly.

Section I of this letter by several law professors has some additional arguments about how to construe the AUMF and FISA in conjunction with each other, but this seems to me the most compelling argument.

It seems to me that Virginia Patriot's heart is not truly in this statutory argument, since he devotes the better part of his piece to the more interesting and difficult constitutional question. If both arguments were close ones, the desire to avoid a difficult question of constitutional law might inform the statutory question, but I just don't think the question of how to construe the AUMF and FISA is that close. This post is long enough, so I'll turn to the constitutional issue in another post.

Barr baiting.

[T]he old prosecutor managed to elicit a crucial concession from Dinh: that the administration's case for its program comes down to saying "Trust me."Article II is clearly superfluous. With a President who can determine the legality of his own actions, what do we need Article III for?"None of us can make a conclusive assessment as to the wisdom of that program and its legality," Dinh acknowledged, "without knowing the full operational details. I do trust the president when he asserts that he has reviewed it carefully and therefore is convinced that there is full legal authority."

According to Wikipedia:

Bear-baiting is a blood sport that was a popular entertainment from at least the 11th century in which a bear is secured to a post and then attacked by a number of dogs.Bear baiting finally was banned in England in 1835, not too many years after American colonists revolted against the monarchy of King George III and established a constitutional republic.

In the most well known form, there were purpose-built arenas for the entertainment, called in England bear-gardens, consisting of a circular high fenced area, the pit, and raised seating for spectators. A post would be set in the ground towards the edge of the pit and the bear chained to it, either by the leg or neck. The dogs would then be set on it, being replaced as they tired or were wounded or killed. For a long time the main bear-garden in London was the Paris Garden at Southwark.

Presumably the folks at CPAC were warming up for the fall elections.

Smoke this as needed.

Friday, February 10, 2006

A cartoonish debate.

Found on the web.

- Quel screw-up.

- This prompts the question: What sort of documentation do you need to import a human head?

- See your home and what it's worth.

Anaheim strikes out.

On the other hand, I can see why the jury might not have credited the City's claim for damages. "City officials said the change cost Anaheim at least $100 million in lost tourism, publicity and so-called "impressions" -- buzz the city gets each time its name appears in the national media in conjunction with a major-league baseball team." That sounds more than a little speculative. Maybe asking for too much hurt the City on liability.

More real estate porn, on its way.

Carol Lloyd writes about some new magazines and TV shows aimed at scratching the real-estate itch. E.g., "LORE, a magazine that touts itself as the Vanity Fair of the real estate set." Here is LORE's home page.

She asks: "[F]or a national obsession so intense that it's become a cliche to refer to photography of nice houses as "real estate porn," it's even more remarkable that no popular media outlet has been created to exploit this wanton interest in all things real estate." It may be a national obsession, but isn't the problem that the markets are all local? And even within those geographic areas, markets are highly segmented. If you own a 3-4BR house, do you really want to spend time looking at 1BR condos? And vice versa. Which is why the other two new offerings Lloyd discusses are both focused on the Bay Area.

Sports news of the day.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Found on the web.

- As Atrios points out, maybe amidst all the talk about blogging ethics we can find some time to talk about why Time passed along White House statements about the defenestration of Valerie Plame which several Time reporters and editors knew then were false?

- Larry Lessig writes about the next battle in the war to make the internet read-only -- in which case, you won't be able to make or see all sorts of things.

What do they stand for?

The White House has been twisting arms to ensure that no Republican member votes against President Bush in the Senate Judiciary Committee’s investigation of the administration's unauthorized wiretapping.Insight magazine, via TAPPED. I really have a hard time seeing the current crowd launching impeachment proceedings, even if they have the cojones to stand up to Rove on this one. The article continues:

Congressional sources said Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove has threatened to blacklist any Republican who votes against the president. The sources said the blacklist would mean a halt in any White House political or financial support of senators running for re-election in November.

"It's hardball all the way," a senior GOP congressional aide said.

The sources said the administration has been alarmed over the damage that could result from the Senate hearings, which began on Monday, Feb. 6. They said the defection of even a handful of Republican committee members could result in a determination that the president violated the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Such a determination could lead to impeachment proceedings.

Over the last few weeks, Mr. Rove has been calling in virtually every Republican on the Senate committee as well as the leadership in Congress. The sources said Mr. Rove's message has been that a vote against Mr. Bush would destroy GOP prospects in congressional elections.It's not clear to me that appearances and photo-ops with the president will necessarily help candidates all that much this year. You would think that a lot of Republicans will be trying to create some distance between themselves and an unpopular, lame-duck president. Even with 55 Senate seats, would Rove cut off his nose to spite his face? (Actually, to keep the ears and eyes in line.) And I've got to think more of them are thinking like Chuck Hagel than are willing to say so out loud:

"He's [Rove] lining them up one by one," another congressional source said.

Mr. Rove is leading the White House campaign to help the GOP in November’s congressional elections. The sources said the White House has offered to help loyalists with money and free publicity, such as appearances and photo-ops with the president.

Those deemed disloyal to Mr. Rove would appear on his blacklist. The sources said dozens of GOP members in the House and Senate are on that list.

Some have raised doubts about Mr. Rove's strategy of painting the Democrats, who have opposed unwarranted surveillance, as being dismissive of the threat posed by al Qaeda terrorists.And then there are those like Hagel who aren't up for re-election this year. And he's not on the Judiciary Committee. Here are the Republicans who are, with the year in which they next face re-election:

"Well, I didn't like what Mr. Rove said, because it frames terrorism and the issue of terrorism and everything that goes with it, whether it's the renewal of the Patriot Act or the NSA wiretapping, in a political context," said Sen. Chuck Hagel, Nebraska Republican.

Specter (PA) - 2010Brownback apparently will be retiring, and I've heard the same about Specter, who was touch and go to run last year. It looks like Rove might have the most leverage over Senators Kyl and DeWine this year, in terms of threatening their own re-election rather than appealing to their desire to maintain Republican control over Congress. Which surely isn't nothing. Time to find out what the oath of office really meant for these folks.

Hatch (UT) - 2006

Grassley (IA) - 2010

Kyl (AZ) - 2006

DeWine (OH) - 2006

Sessions (AL) - 2008

Graham (SC) - 2008

Cornyn (TX) - 2008

Brownback (KS) - 2010

Coburn (OK) - 2010

Shorter Attorney General Gonzales.

What we did was legal, or, in our opinion, could have been legal. Since there are arguments on both sides, we will rely on our opinion. However, we won't let a court decide the question, because then we wouldn't be able to rely on our own opinion.Brovo, Jack Balkin.

We won't answer hypothetical questions about what we can do legally or constitutionally. We also won't tell you what we've actually done or plan to do; hence every question you ask will about legality be in effect a hypothetical, and therefore we can refuse to answer it.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Graven images.

Found on the web.

- "[F]olks join the CIA thinking they will become Jack Ryan or Mitch Rapp. Within a few short years they realize they are Dilbert." Larry Johnson on Porter Goss's house-cleaning at the CIA.

- Looks like Tookie Williams' supporters are not only ones gullible enough to think that a Nobel Peace Prize nomination means something. Balloon Juice says, "Heads are going to explode." Indeed. I'm sure Volokh will set Cole straight.

- A Ukrainian Spetsnaz veteran returns from a year of security work in Iraq to open a beauty parlor in his hometown.

- Yglesias: "When we honor a recently dead person, we always leave it up to the judgment of the deceased's close friends and families to use their best judgment as to how that person would want his or her life to be commemorated. Since when did these arrangements come to be subjected to criticism by random pundits? I hope to God that if through some misfortune I drop dead tomorrow, the organizers of my funeral won't shy away from mentioning the small matter of the political causes I've spent my entire (and admittedly brief) professional career fighting for. "

No check, no balance?

It's February, 2009, and someone in the NSA leaks to the Washington Times that President Hillary Clinton (she dropped the Rodham to get elected) has started a new program of listening in on domestic phone calls. President Clinton holds a press conference, and says that she has received (unspecified) intel that has persuaded her that terrorists inside the United States may be plotting another attack, and she needs to do whatever it takes to defend the country. Trust her. President Bush established that Article II gives her the executive power to do what she needs to do in the name of national defense, so everyone should just accept that Congress has no role here. The Washington Times is aiding the enemy by publishing leaks, but she won't comment on allegations that communications involving prominent Republicans have been intercepted.

No constitutional problem here, right? If the voters elect Hillary as commander-in-chief -- not something I'm in favor of, let's be clear -- you all think that Article II empowers her to act this way?

.

No word if Danes are protesting.

But wait! There's more! The Simpsons have gone Arabic too.

Obviously, this is an important story, given the way that our nation's senior diplomats tend to draw on The Simpsons for policy inspiration.

Greatest Budget Hits (a re-release).

Remember, this is how these folks play the budget game. (The basic insight here is Mark Schmitt's, bless his wonky heart.) Bush proposes cutting popular things, like Sesame Street and Amtrak, knowing full well that Congress will never do it. Bush gets to pose as a tough-minded deficit warrior, and Congress gets to preen as it saves the good stuff from the cutting block. For politicians, it's a win-win.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]