Thursday, June 30, 2005

Squishy centrism.

D.C. Pundit Bonus Coverage

David Ignatius's column in today's WaPo is full of all sorts of interesting observations about how repressive governments help us fight terrorism, but then he wraps up with this insipid closing: "America has a lot of chips on the table now, betting on outcomes that are uncertain. Bush should be wary of adding to these risks without examining them very, very carefully." Is there any point in urging that Bush should examine something -- anything -- "very, very carefully"? The electorate voted for steely resolve, not thoughtful deliberation.

Standing on principle, but only so far?

Cooper evidently was prepared to go to jail rather than reveal his source. According to the Washington Post, "told Reuters that he would rather Time not turn over his notes but acknowledged that the magazine had its own obligations to consider."

Is it not a little odd that Cooper is prepared to disobey a federal court, but not his own employer? If the principle is worth serving time for, might it not also be worth losing his job?

What has Roger Ebert done for the culture?

In the path from mere critic to cultural institution, Ebert has adopted a pose at once populist and condescending.... Instead of seeking to broaden his reader's experience of movies, he presumes to approximate it, in the process lowering the culture's standards for what makes a good movie.

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

How do you say "bling" in Russian?

It could be an international incident of sorts, a misunderstanding of Super Bowl proportions. Or it could be a very, very generous gift.The Boston Globe (via a tip from B.).

Whatever the case, New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft is out one championship ring, and President Vladimir Putin of Russia has scooped up some very flashy bling.

At a meeting of American business executives and Putin on Saturday in Russia, according to Russian news reports, Kraft showed his 4.94-carat, diamond-encrusted 2005 Super Bowl ring to the Russian president, who, after trying it on, put it in his pocket and left.

Tuesday, June 28, 2005

Bear with me.

Saturday, June 25, 2005

Boonville: A review.

The blurbs on Robert Mailer Anderson's first novel, Boonville

At the center of the story is John Gibson, bred in south Florida and not too long ago graduated from the University of Miami. His grandmother, the black sheep of the family, passes away and Gibson chucks his life in Miami to move to her cabin in Boonville, California, a town of 715 oddballs and eccentrics north of San Francisco and south of Mendocino.

Anderson does a good job painting the town of Boonville and its assorted inhabitants, though one beef I have with the book is that several of the characters are drawn without sympathy. For example, John's girlfriend in Florida, Christina, seems like such an unpleasant sort that it's hard too see why he would date her, let alone as long as he did, and it seems unlikely when he pines for her. I found it too easy to see the gears of Anderson's plot moving too easily behind Christina and a few other characters. Had Boonville, like (say) A Confederacy of Dunces, gone over the top, maybe Anderson could have gotten away with this sort of thing, but I thought he got stuck somewhere between satire and realism.

More generally, Anderson uses the book, and John's internal life, as a platform to share a whole bunch of odd thoughts about pop culture and modern living. All too often, these asides did not seem to advance the plot or his characterizations. Maybe he's gotten all of this out of his system, and his second novel will be one to watch for. I don't regret reading Boonville, but -- sorry, Jonathan Lethem* -- if I were going to read a novel set in Northern California, I'd stick with Vineland.

What do I know? If you want buy it, click through the link above to send me a few pennies.

* Boonville's back cover: "A brilliant new voice--twitchy, corny, sly, cackling, and sad, but most of all, racing with vitality and goosing you to keep up. Boonville is the creepy and hilarious coming-of-age story the territory deserves--not your parents' Vineland, but your own." --Jonathan Lethem

What Rove is up to.

INDEPENDENTS AND BUSH: I guess some might call me an Independent, in as much as I've backed Democrats and Republicans in the past. Backing Reagan and the two Bushes as well as Kerry and Clinton puts me somewhere in the center, I suppose. I'm more of a conservative of doubt in my own mind. Whatever. This new poll contains something interesting to me:The levers of power are all in GOP hands these days. For the next three years, Rove doesn't have to worry about independent or Democratic support, except insofar as he needs his side to win enough seats in the mid-term election to keep its majority in Congress -- although perhaps Rove is thinking that Bush is well and truly a lame duck after the '06 elections, and needs to get things done now. Hence the strategy of polarization. Rove's comments the other day were no accident, they were a calculated effort to raise the temperature. In order to keep Republicans with him, Rove is fomenting divisiveness and discord. Expect it to continue. In this environment, it's that much less likely that Republicans will do display the independence and principle that (e.g.) Sen. Voinovich did in opposing Bolton's nomination. They are less likely to want to do so, and they will be more constrained by their fellow party members. The country may be at war, but Rove -- and Bush -- are sacrificing national unity for the sake of partisan advantage.Among Republicans (36% of adults registered to vote in the survey), 84% approve of the way Bush is handling his job and 12% disapprove. Among Democrats (38% of adults registered to vote in the survey), 18% approve and 77% disapprove of the way Bush is handling his job. Among Independents (26% of adults registered to vote in the survey), 17% approve and 75% disapprove of the way Bush is handling his job as president.The disapproval levels of Independents and Democrats are now indistinguishable, but the Republican bloc is solid. This strikes me as a direct result of the Rove strategy of brutal partisanship, Christianist pandering, and general fiscal and military fecklessness. Some readers have said that my criticism of the administration makes me sound like a liberal these days. Well, from these results, I'm not the only one being pushed by right-wing extremism into opposition.

The DTs will be no fun either.

I think that many in the majority party are finding themselves in the same psychic shape as alcoholics a few months before they finally seek sobriety, except for George Bush, who apparently does not have a clue. With alcoholism, other people can see that the alkie is, to quote one of my friends, in a state of pitiful and incomprehensible demoralization; but it takes what it takes for the alcoholic to realize that. This is why we have Karl Rove saying that when liberals saw the savagery of 9-11, we wanted to give the terrorists aid, comfort, and aromatherapy....For reasons best put elsewhere -- if I find them I'll change this to a link -- I think Rove had rational (if slimy) reasons for what he said, but there's some lower truth to what Lamott says.

Rove's behavior this week reminds me of three things, besides my own sorry alcoholic collapse: one is what my very wise friend Gil says-and Gil has been sober since before God-that there are three stages in the disease: fun, fun and trouble, and trouble. Fun, for the White House, was the fall of Baghdad and Mission Accomplished. Fun and Trouble held, up until a month or so ago: you had huge body counts, grave global dismay, etc, but you also had the elections here and in Iraq, with all that courage and the purple fingertips. Now?

Well, I don't see where the fun is anymore: I think we are now leaving the fun and trouble stage.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Signs of the Apocalypse, Real Estate Dept.

(Warning: Link may not endure.)

Thursday, June 23, 2005

Brad DeLong has met his match and it is our local grocery store.

Now I want to go to Norway.

Norwegians, as I discovered during a four-day hiking expedition to the wind-swept Hardangervidda National Park a few summers ago, embrace the outdoors with an almost reverential fervor. During a trek with a hiking companion, Tim Goldsmid, I met Norwegian hikers of all shapes - from a family with a pair of blond-haired children in tow, bobbing as they tried to keep up with their parents, to an older couple sharing sips of tea out of a stainless steel thermos on a rocky outcrop along the trail. While we were on vacation thousands of miles from home, many Norwegians often escape for a one- or two-day wilderness trips. Outdoor recreation is a way of life there.OK, sign me up.

"Hiking is a very special tradition here, because so many people live close to nature in Norway," said Anne Marie Hjelle, the director of the Mountain Touring Association, known as DNT. "Starting in kindergarten, children spend time in parks and the forest. Nature is all around us here, and it's something Norwegians feel very special about."

But while Norwegians fan out into the national parks in the summer, the country escapes much of the tourist crush that deluges Europe's more populous mountain regions. The well-traveled destinations in the Alps - among them, Chamonix, France, and Zermatt, Switzerland - bubble over with vacationers ogling the snow-crowned peaks. Norway offers the perfect antidote: a remote and ragged landscape carved by majestic fjords into vertiginous peaks and verdant valleys that remain largely out of the path of the tourist stampede.

Alan Turing.

Wednesday, June 22, 2005

Yo.

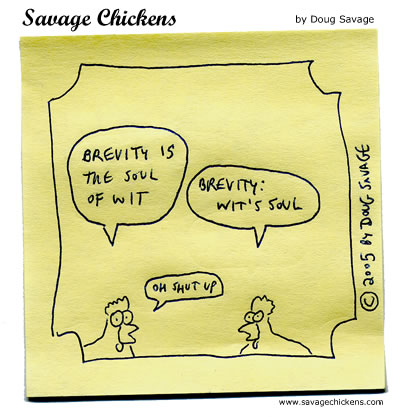

Savage Chickens.

Tuesday, June 21, 2005

A Good Life: A review.

My grandmother gave me a copy of Ben Bradlee's A Good Life

His memoir is full of interesting stories, delivered in the brisk, efficient prose you would expect. What he is not is introspective. Bradlee recounts that after he left the service, he

enrolled in a couple of night courses in the New School for Social Research in Greenwich Village, one of them in fiction writing, taught by James T. Farrell, the author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy. Just in case the great American novel was locked somewhere between my belly and my soul. I was keeping all options wide open at that time in my life. But this option soon closed. Twice a week, our assignment was to write 1,500 words of fiction, and I couldn't write 15 words that I had to make up. I could exaggerate my own experience a little, but exaggeration made me feel untruthful. My "fiction" was without exploration of motive or emotion, and in a brief student-teacher session Farrell put me out of my misery. There was a certain facility for describing what I had seen, he said, but nothing interesting when it came to describing emotion. He was not the last to make that observation.A Good Life 96-97 (New York 1996).

Indeed, Bradlee's accounts of his first two marriages and his third marriage to Sally Quinn are not particularly illuminating. But A Good Life has much more to offer. For example, with the ongoing debate about the Downing Street Memo and how we got to this point in Iraq, Bradlee's account of the fight over the publication of the Pentagon Papers is a worthwhile reminder that the government will often use the pretext of national security interests to hide embarrassing facts. Bradlee writes -- and I had not realized -- that 18 years after the Solicitor General of the United States, former Harvard Law School dean Ernest Griswold, argued to the Supreme Court that publication of the Pentagon Papers would threaten national security, he confessed that the government's case was specious. (Griswold corrected the record in an Op-Ed piece in, where else, The Washington Post. See page 323 of A Good Life.) Good thing for all of us that Bradlee's newspaper had the moxie to keep fighting.

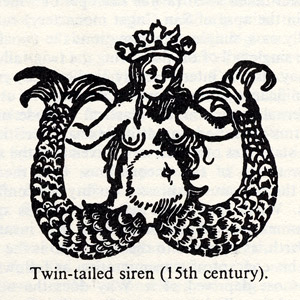

When the siren calls me, it sounds like caffeine.

to this:

Only he's got lots of interim stages.

Sunday, June 19, 2005

No one has ever been more grateful to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Principles of American Nuclear Chemistry: A review.

Thomas McMahon was the Gordon McKay Professor of Applied Mechanics and professor of biology at Harvard University; he also wrote some wonderful, quirky novels. His first was Principles of American Nuclear Chemistry: A Novel

One might say that Principles of American Nuclear Chemistry is the story of a childhood and a troubled marriage set in the Manhattan Project, in Oak Ridge and Los Alamos. But it's more fitting to say that the novel is about the thrill and dislocation of the Manhattan Project, of the odd community of scientists that was formed and the dislocations in their personal life that accompanied and fueled the creation of the atomic bomb. The relationship between McMahon's narrator and his scientist father is not fleshed out at all, but we watch as his mother stays in Boston rather than move to Tennessee or New Mexico, and as his father takes up with Maryann, an Oak Ridge secretary. We also see a host of other famous scientists, whose faux names are no disguise. I spotted Fermi, Bohr, Oppenheimer, Lawrence, and others. None are fully developed, but through them we glimpse the Manhattan Project -- once the new new thing, but now receding into history.

Saturday, June 18, 2005

Who needs sports journalism?

Q: I fully expect that after Clemens wins his 333rd game, in his press conference, he will take off his cap and will pull back his hair – revealing an identical 333 burned into his scalp; thus fulfilling the prophecy. This will immediately be followed by all the reporters in the room melting away, with their bones exploding like in "Raiders of the Lost Ark."Can't say I watch PTI much, but that sounds about right to me.

–William S., New York

[Bill Simmons]: The best part about this would be Wilbon and Kornheiser discussing the incident on PTI the following day.

Kornheiser: "All right, Wilbon, some sad news last night, we found out that Roger Clemens was indeed the anti-Christ, as nearly 50 reporters – including some of the best this business had to offer – were melted to death after the prophecy was fulfilled. Wilbon, you were there, but you were able to get out of the room in time … how does this affect Roger Clemens' legacy?

Wilbon: "Oh, it absolutely affects his legacy! There's no question! Tony, he killed 50 media members! He melted them to death!"

Kornheiser: "But he's still the greatest pitcher of the last 50 years!"

Wilbon: "Tony, he's the anti-Christ!"

Kornheiser: "I don't see how that affects his Hall of Fame resume – 333 wins, over 4,500 strikeouts, 7 Cy Youngs … "

Wilbon: "Tony, he's a mass murderer! Pete Rose isn't in the Hall of Fame for gambling on baseball, this guy melted 50 people! He almost killed me!"

Kornheiser: "Well, that shouldn't affect what he accomplished on the field. Ty Cobb wasn't a nice guy either. [We hear a bell in the background.] Moving to the NBA Finals … "

Dark Voyage: A review.

As I suggested at the time, I was a little disappointed by the last Alan Furst novel I read, but I loved Dark Voyage

Alan Furst's website, with reviews and other fun stuff, is here. If you like reading about Tangier and the coast of Africa in Dark Voyage, I recommend Desert War: The North Africa Campaign 1940-43

A Secret Life: A review.

Even with all the Alan Furst and Phillip Kerr, I'm still open to some literary espionage, and so I recently picked up a copy of Benjamin Weiser's A Secret Life

Weiser, a Washington Post writer, has done a tremendous job of working with materials from the CIA's archives, which he managed by arranging for a CIA veteran to do the research. (After this work passed through the CIA's security review, Weiser was then free to write his story.) Although I tired a little of reading the correspondence between Kuklinski and his handlers, one comes to appreciate the importance of the exchange to the spy, who can speak in candor to no one else. The CIA let Weiser explain far more of the tradecraft than I would have guessed. Notwithstanding the excitement of much spy fiction, the real thing involved an awful lot of tedious driving to lay the foundation for rare exchanges.

Kuklinski gained notoreity after his defection, and was sentenced to death by Jaruzelski's government. Well after the Berlin Wall came down, many Poles felt Kuklinski was a traitor. The last chapters of A Secret Life focus more on this controversy than on Kuklinski's life in the West, and it's good stuff, although perhaps these chapters warrant a book of their own. (Those who enjoy this part of A Secret Life might take a look at Lawrence Weschler's profile of the former spokesman for the Jaruzelski regime, Jerzy Urban, who makes a brief appearance, here and who has found unexpected financial success publishing a newspaper in recent years, in Weschler's Vermeer in Bosnia

A 1998 article from the Warsaw Voice about the controversy of Kuklinski is here. More coverage of him, including several pictures, is here. A memorial mass following Kuklinski's death is described here. Several obituaries are linked here.

Friday, June 17, 2005

Hiyao Miyazaki.

Quoting from a recent New York Times article, Byzantium's Shores posts about the particular aesthetic of Hiyao Miyazaki's films -- the latest, Howl's Moving Castle, is in the theaters now:

We've just discovered My Neighbor Totoro. We had it on a five-day rental, and I'm just back from returning it to the video store before they closed at 10 p.m. It's terrific stuff, and a welcome change of pace from the Pixar Universe in which we so often find ourselves in this household. I'm looking forward to his other films.[A] conscious sense of mystery is the core of Mr. Miyazaki's art. Spend enough time in his world - something you can do at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan, which is presenting a sumptuous retrospective of his and Mr. Takahata's work - and you may find your perception of your own world refreshed, as it might be by a similarly intensive immersion in the oeuvre of Ansel Adams, J. M. W. Turner or Monet. After a while, certain vistas - a rolling meadow dappled with flowers and shadowed by high cumulus clouds, a range of rocky foothills rising toward snow-capped peaks, the fading light at the edge of a forest - deserve to be called Miyazakian.That is absolutely true. After watching Miyazaki's films for several years, there really are times when I look at the world around me and think, "This could have come from one of his movies." Usually it's a particular sky or cloudscape that does it.

What I adore about Miyazaki's visuals, beyond the sheer majesty of the compositions themselves, is the attention to small details you might not even notice. (This is also something I've admired in George Lucas.) In My Neighbor Totoro, for example, there's a scene where a bicycle messenger visits the central family, and we see his bike parked outside the house in what must be a two-second shot. But it's not a static shot, as it would be for any other filmmaker: Miyazaki actually animated the front wheel, lazily turning in the breeze.

No sacrifice.

And I know college students who have heard of President Kennedy but not of anything he ever did except get assassinated. They have never heard JFK's inaugural promise: that America would "pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to ensure the survival and the success of liberty." But President Bush remembers that speech, and it's lucky he does.If President Bush remembers the speech, he doesn't remember it very well. Kennedy led by warning Americans that they might have to make sacrifices "to ensure the survival and success of liberty." Bush is too weak a leader to ask for such sacrifice, so we get wartime tax cuts and deficit spending. We get National Guardsmen and Reservists forced to extended service and no draft. He is all about having our cake and eating it too. No one will be quoting Bush's inaugural addresses in forty years; they are full of easy ideas, not great ones.

FWIW, I agree with Juan and Gelernter more generally about the importance of history.

Thursday, June 16, 2005

A worthy cause indeed.

Tom Watson is rallying support for Mukhtaran Bibi -- go to Tom's site and do what you can.

eta: Watson has an update. And more about Mukhtaran Bibi.

Before he was a star.

"[We] have been led in Mesopotamia into a trap from which it will be hard to escape with dignity and honour. [We] have been tricked into it by a steady withholding of information. The Baghdad communiqués are belated, insincere, incomplete. Things have been far worse than we have been told, our administration more bloody and inefficient than the public knows... Our unfortunate troops,... under hard conditions of climate and supply, are policing an immense area, paying dearly every day in lives for the willfully wrong policy of the civil administration in Baghdad."T.E. Lawrence, Sunday Times of London, August 22, 1920, via Andrew Sullivan

Good tunes.

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

Now that you say it, it does sound familiar.

It seems that some Republicans won't stand up to Christian fanatics at the Air Force Academy intent on harassing Jewish cadets, while others won't take a public position on whether or not lynchings were bad, lest they alienate their racist constituents. It's almost as if they're a white, Christian party that's not all that sensitive to the concerns of America's racial and religious minorities or something.

Murakami in the NYT.

But surely it is Murakami's departures from traditional Japanese literary forms that have helped him become popular elsewhere.Still, for all his success, Mr. Murakami, 55, speaks with a bitter edge toward the Japanese literary establishment, which has kept him at bay as much as he has distanced himself from it.

"I don't consider myself part of the establishment," he said. "I don't deal with the Japanese literary circle or society at all. I live totally separate from them and still rebel against that world."

Indeed in Japan, the traditional literary critics regard his novels as un-Japanese and look askance at their Western influences, ranging from the writing style to the American cultural references. (In the United States his work is taught in colleges and has been reviewed by John Updike in The New Yorker.)

My thoughts about Kafka on the Shore, such as they were, are here. OK, actually I didn't post any thoughts there, but I did post a bunch of good links.During a recent interview at his office, a barefoot Mr. Murakami, wearing jeans and an orange shirt, spoke on a variety of subjects, from his place in contemporary literature to his writing habits. He appeared at ease, since he was preparing to take one of his periodic breaks, both from his writing and from Japan. He will spend the next year at Harvard as a writer in residence.

"Kafka on the Shore" tells two alternating and ultimately converging stories. Mr. Murakami said he had become bored writing about urban dwellers in their 20's and 30's, and so in "Kafka" he decided to create two different types: a 15-year-old boy named Kafka Tamura, who runs away from home to rural western Japan; and a mentally defective man in his 60's, Satoru Nakata, who has the ability to talk to cats.

The novel has Mr. Murakami's signature surrealism, as fish rain from the sky, and characters named Johnnie Walker, a cat killer, and Colonel Sanders, a pimp, play critical roles.

Like his other novels this one is filled with references to American culture, but Mr. Murakami said he regarded Coca-Cola and Colonel Sanders, for instance, as worldwide references. "References such as Colonel Sanders or Johnnie Walker are in a way Western and everybody tends to fix their eyes on that," he said. "But as for the essence of a story, my stories have strong Japanese or Oriental elements. I think the structure of my stories is different from so-called Western stories."Hard to understand why the traditional literary critics in Japan don't like him, eh?

His storytelling, he said, "does not develop logically from A to B to C to D, but I don't intentionally break up or reverse episodes the way postmodernists do. For me, it is a natural development, but it is not logical."

Mr. Murakami's attachment to American literature is longstanding. As a high school student in Kobe, in western Japan, he read, in the original, Kurt Vonnegut, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Truman Capote and Raymond Chandler. Like many Japanese of his generation, he became passionate about jazz and rock.

"American culture," he said, "became ingrained in my body." By contrast, he never read Japanese novels until he was an adult. "I didn't read them when I was young because they were boring," he said.

In Japanese, Mr. Murakami speaks in declarative, sometimes blunt, sentences that convey exactly what he means. He eschews the expressions that most Japanese use to soften their speech and that tend to make the language vague.So I wish someone would hurry up and translate After Dark. (Thanks for the tip, G.)

His writing is infused with the same directness, which makes it easy to translate into English, but which many critics here say lack the richness of traditional literary Japanese. And there are readers here who say that his writing reads as if it had been translated from English into their own language.

Mr. Murakami - who translated English-language novels into Japanese before he wrote them, and two years ago offered a new Japanese translation of "The Catcher in the Rye" - said he has chosen to write in a "neutral" Japanese, explaining:

"There was a notion in Japan that novelists write in a certain style. I totally ignored it and created a new style. Therefore, in Japan, there was resistance. I was much criticized."

When "Kafka" was published in Japan in 2002, it was popularly acclaimed. But some of this country's top literary critics dismissed it as an example of the impoverishment of Japanese literature, with language devoid of depth and richness.

Among readers, however, his novels are wildly successful, allowing him to write fiction full time - something he said he had never imagined possible.

He wrote "Kafka" in six months, starting, as he usually does, without a plan. He spent one year revising it. He follows a strict regimen. Going to bed around 9 p.m. - he never dreams, he said - he wakes up without an alarm clock around 4 a.m. He immediately turns on his Macintosh and writes until 11 a.m., producing every day 4,000 characters, or the equivalent of two to three pages in English.

He said that his wife has told him that his personality changes when he is writing his first draft, and that he becomes difficult, nontalkative, tense and forgetful.

"I write the same amount every day without any day off," he said. "I absolutely never look back and go forward. I hear Hemingway was like that."

Unlike Hemingway, Mr. Murakami leads a healthy lifestyle. In the afternoons, to build up his stamina to keep writing, he works out for one or two hours. Whenever he is in Tokyo, he also visits old-record stores, especially ones in the youth mecca of Shibuya, which appears to be the unnamed setting of "After Dark," published last fall to relatively little attention here.

A short novel, which has yet to be translated into English, "After Dark" centers on the stories of several characters over the course of one night as seen, neutrally and coldly, through a camera eye. The novel could be easily adapted into film, unlike Mr. Murakami's other novels. He has resisted selling his novels to filmmakers, though he said he would hand them over unconditionally to Woody Allen or David Lynch.

He may now be enjoying the big break in the United States that he has worked for since spending two years in the country in the early 1990's.

"I went to New York myself, found an agent myself, found a publisher myself, found an editor myself," Mr. Murakami said. "No Japanese novelist has ever done such things. But I thought I had to do that."

He added: "I wanted to test my ability overseas, not being satisfied with being a famous novelist in Japan."

Monday, June 13, 2005

The Siege of Budapest: a review.

A kind and loving soul who will go unnamed here gave me a gift certificate to one of our local booksellers, which I used to buy Krisztian Ungvary's The Siege of Budapest: One Hundred Days in World War II

I've never known as much about the Russian offensives at the end of World War II that led to the fall of Berlin. In late 1944, Hitler placed a great emphasis on defending Hungary, in the hopes that slowing the USSR's advance could somehow drive a wedge to separate the Allies. Notwithstanding some local successes, the German and Hungarian forces could not prevent the Soviet forces from encircling Budapest. Defending forces in the capital could have escape to the northwest, and perhaps the capital could have been evacuated, but the German command -- in particular, Hitler -- chose to sacrifice those forces, and the city, in order to slow the Soviet advance towards Vienna. The result was a brutal siege, similar to what happened to Leningrad, Stalingrad and Berlin, except that in the former instances most civilians were evacuated, and in the latter instance the fighting lasted days or weeks, not months. The casualties and damage were truly horrific.

Taking advantage of newly available archives, Ungvary has written a comprehensive and moving account of the siege. Some of it is slow going -- for example, for those of us unfamiliar with Hungarian geography, the movements of military forces can be hard to follow, and the maps do not always help. But do not be deterred; the most compelling parts of the book are those dealing with the privations of those trapped inside Budapest, soldier and civilian, Christian and Jew, and the tale of the battle is only the predicate for their story.

While their own leaders were not without fault, the pity of the Hungarians was to find themselves between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. After finishing The Siege of Budapest, I came across this:

I thought of what Romania's late ambassador in Washington, Corneliu Bogdan, had told his friends--"The West did not lose Eastern Europe at Yalta. It lost it at Munich."--when the West abdicated responsibility for Eastern European security to Hitler and Stalin.Robert D. Kaplan, Eastward to Tartary 41 (New York 2000). After the siege came the Iron Curtain.

Nor does the Canadian Constitution enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics.

Truly, he is on crack.

When evolutionary explanations run amok.

I think natural selection must have greatly rewarded the ability to reassure oneself in a crisis with complete bullshit. It's not hard to see how: if two early hominids are both fleeing a large, faster predator from which there is no escape, and one of them is sincerely thinking "I'm gonna be OK, I'm gonna be OK, the gods are watching over me, I'm gonna be OK" and the other is thinking "AAIEE! I'm dinner! I'm an entree! AAIEE! I'M GONNA DIE!" it's not hard to guess which one will give up first and wind up getting dragged around by his entrails. Indeed, inventing reassuring bullshit may be humankind's keenest survival skill. And now that we are our own greatest predator, it will probably kill us all.

Keeping hope alive.

Sunday, June 12, 2005

Berlin Noir: a review.

In the bookstore to pick up a copy of Alan Furst's latest, I found this Phillip Kerr's Berlin Noir

Like Furst's novels, Kerr does a wonderful job of conveying the sense of time and place. As some of Furst's earlier novels did with the Soviet Union, the first two novels play on the factional intrigue within Germany, and the latter comes as the wartime Allies shift into the Cold War. The noir style is an excellent fit for the corruption of Nazi Germany, and the lawlessness of postwar Vienna.

If I may quibble -- and it is just that -- while reading the trilogy, it is sometimes too hard to suppress one's knowledge of what is to come, especially for Germany's Jews, whose plight is a theme throughout the trilogy. Gunther's thoughts about what is happening to the Jews have a tinge of hindsight to them. One sees Kerr mastering this theme over the course of the trilogy: In March Violets, it seems a little forced; in The Pale Criminal, less so, as Kerr does a better job of integrating it into the plot; and in A German Requiem, set after Nazi crimes have been exposed, Gunther's consciousness is entirely appropriate.

I think I saw that Kerr was one of Granta's best young English novelists some years back, and I enjoyed his writing quite a bit. Recommended, especially to you Furst fans.

Saturday, June 11, 2005

Completely unsubstantiated, so far as I know.

Friday, June 10, 2005

News flash!

-- An anonymous cable news employee, quote courtesy of Kevin Drum.

Thursday, June 09, 2005

It's like Vietnam all over again.

Enough, already.

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

A white buffalo in Kentucky.

If you're tired of thinking clearly.

How did they get from there to here?

Perhaps the most insistent teaching of the Catholic church today is a conception of family life. Apart from priests, nuns and homosexuals, the call to procreative marriage has been put at the very center of what it means to be a faithful Catholic. As you see in that passage above, the very Incarnation is deployed to defend marriage and procreation as a central human goal. And yet, when you read the Gospels, you find something very strange. Jesus barely mentions marriage. He never married. He demanded of all his disciples that they abandon their own families and wives, without even saying goodbye. He was openly contemptuous toward his own mother and father in adolescence and early adulthood. His fundamental response to adultery was forgiveness of the adulterer and suspicion of the morally superior. His contemporaries must have regarded him as illegitimate, since he was conceived out of wedlock. So this illegitimate, single man who broke up family after family, whose closest female friend was a childless former prostitute, who scandalously stayed alone in the home of two unmarried women, who offended every family value of the time ... has been turned into the chief architect of "family values!" I'm not saying that building families is something alien to Christianity. We are not all called to wander through the fields preaching salvation and telling people to abandon their spouses and children. I'm not saying that procreative marriage isn't a glorious thing. What I am saying is that the over-powering fixation on marriage, family life and procreation has overwhelmed the deeper and more unsettling priorities that Jesus obviously stood for and proclaimed. The gulf between the priorities of the Gospels and those of the hierarchy of the Church on this score is both wide and deep.I really have a hard time explaining not only how the Church got here from there, but also why these issues are so central right now.

A Catholic joke.

Leonardo Boff, Hans Kung and Benedict XVI all die on the same day. They arrive at the Pearly Gates and St Peter welcomes them and says that Jesus wants to see each of them individually. Boff is first to go in to see Jesus. After half an hour, Boff comes out, shaking his head, and muttering, "How could I have been so wrong?" Kung is next. Same deal. After a while, Kung too emerges, head in hands: "How could I have been so wrong?" Benedict is next. After half an hour, Jesus himself comes out and groans: "How can I have been so wrong?"

This used to be so simple.

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

Not an Amis fan.

Sexy, clean coal.

Malthus was onto something.

At the time Elvis Presley died in 1977, he had 150 impersonators in the US. Now, according to calculations I spotted in a Sunday newspaper colour supplement recently, there are 85,000. Intriguingly, that means one in every 3,400 Americans is an Elvis impersonator. More disturbingly, if Elvis impersonators continue multiplying at the same rate, they will account for a third of the world’s population by 2019.

Present at the creation.

What mandate?

Or, they can't stand him.

That aside, Tomasky's piece reminds me of a question I've thought about from time to time, going to the relationship between daily media and history's judgment. Most (if not all) of the opinions and analysis that you get from television, newspapers and weekly magazines is emphemeral, and their conventional wisdom -- to my mind -- has little weight when historians sit down to do their thing. With a few years of perspective, much of what preoccupies us today will seem silly, or obvious, or both. Which tends to suggest that even if Tomasky is right, the sorts of hit pieces that he's talking about won't matter much.

Maybe this is wrong, and today's conventional wisdom because the first draft of history.

Saturday, June 04, 2005

Another wine recommendation.

My new favorite blog.

Friday, June 03, 2005

How are those Bohemian Alps, anyway?

We need better bluster.

Anyone who supports this war and will not fight in it, no matter how they defend it, is going to be regarded as less than seriously by the vast majority of Americans.If only that were so. It's not like any of the Republicans leading us into this war would fight in it. Somehow, they are seriously regarded by most Americans.

It could be so much worse.

Thursday, June 02, 2005

Truer words.

[I]f I had a dollar every time some left of center person said that we need to find ways to connect with people by turning progressive issues into moral issues then I could purchase the Soros empire.Don't you need to be a trained professional to do that? We bloggers are mostly good at telling other people what they should be doing.

Stop talking about what people need to be doing. Show us how it's done.

Writers from Oz.

When I'm in bookshops here in America, I often keep an eye out for Australian titles. You see quite a few, and I'm sure you can guess which authors tend to show up most often. However, there is one Australian author whose work I see far more often than any other and if that sort of visibility is any guide, then that person is by and away the most successful Australian author in America.And that author is . . . Garth Nix.

Who? I have a thing for Aussie fiction, and have enjoyed books by Peter Carey, Tim Winton, Murray Bail, Delia Falconer, David Foster, and many others, but I can't say I've ever heard of Mr. Nix. What am I missing?

Congratulations, Xeney.

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

Checks and balances.

We don't have to admire Mark Felt to appreciate what he did.

East to Nevada.

A couple of weeks ago my dad pointed out that there is only one major route out of California over the Sierra Nevada if you are north of Bakersfield. That road is Interstate 80. Other roads cross the mountains, but in a tentative, almost exploratory way. Eighty is the way in and the way out. The roadway has been blasted with cold and heat. And if, while you're climbing it, you happen to remember, as I did, that this is the one eastern crossing out of northern California, the route somehow seems unduly fragile, cutting its way through time.Nowhere have I ever had that problem as much as in crossing Nevada (though I've never been across West Texas).

It was fitting to have to beat my way out of the state against a headlong storm of rain and wind just a few degrees above ice and snow. The weather sounded an appropriately epic note for the beginning of a drive across country. And yet when we made it down at last into Reno and past Sparks and out into the open sea of sage, it struck me once again how un-epic the trip has become. I always tend to think of the whole crossing at once - from California to upstate New York. But out in the open of Nevada, heading north to Winnemucca, for instance, the sense of the whole slips away, and there we are, on a well-paved, empty patch of road, as if we were driving only from a nearby ranch exit - "No Services" - to the neighboring town.

Driving across Nevada, a few names cling as you pass - Pumpernickel Valley, Starr Valley - but what sticks in your mind is the look of the country, the floating hulks of far-off mountain ranges to the north and south. The Humboldt River was over its banks along much of the route. There was water standing everywhere, and the mountains in the distance were still thick with snow. Where there were cattle, they stood deep in the new grass.

Sometimes, dropping into one of those valleys, I caught sight of a double track making headway straight across the sage and disappearing in the distance. It might have been made by a pickup, but I imagined it was made by an old ox-drawn wagon. It was another one of those encounters with an inconceivable past, a moment when the pure obstinacy of humans rises up in all its force. Rolling along at 70 miles per hour with perfect cellphone coverage and the sound of a recorded book filling the cab of the pickup, I was nevertheless struck by how suddenly we could drop into the here-ness of place simply by pulling over to the side of the road, turning off the engine and walking off the asphalt.

I wondered whether those earlier travelers, whose greatest threat was slowness, not speed, were ever overwhelmed by the particularity of the ground they covered, or whether they kept their minds leaning constantly forward. A trip is always an abstraction, in some sense, a way of diverting attention from the step after step, the mile after mile.

Yesterday Japan, Today Boston, Tomorrow the world!

Me, I've never even heard of Andrea Levy's Small Island.

'Men clearly now know that there are some great books by women - such as Andrea Levy's Small Island - they really ought to have read and ought to consider "great" (or at least good) writing,' the report said. 'They recognise the titles and they've read the reviews. They may even have bought, or been given the books, and start reading them. But they probably won't finish them.'Men have made progress in at least one area, though:

The research was carried out by academics Lisa Jardine and Annie Watkins of Queen Mary College, London, to mark the 10th year of the Orange Prize for Fiction, a literary honour whose women-only rule provoked righteous indignation when the competition was founded. They asked 100 academics, critics and writers and found virtually all now supported the prize.

But a gender gap remains in what people choose to read, at least among the cultural elite. Four out of five men said the last novel they read was by a man, whereas women were almost as likely to have read a book by a male author as a female. When asked what novel by a woman they had read most recently, a majority of men found it hard to recall or could not answer. Women, however, often gave several titles. The report said: 'Men who read fiction tend to read fiction by men, while women read fiction by both women and men.

'Consequently, fiction by women remains "special interest", while fiction by men still sets the standard for quality, narrative and style.'

Jardine said: 'When pressed, men are likely to say things like: "I believe Monica Ali's Brick Lane is a really important book - I'm afraid I haven't read it." I find it most endearing that in 10 years what male readers of fiction have done is learn to pretend that they've read women's books.'The Guardian, via Bookslut.

Get out.

Certainly every parent today has had the experience of begging a child to go outside. The child always asks, "And do what?" And we always say, "Climb a tree!" From the way we talk about it, all we did as children was climb trees, build treehouses and swing on vines. We were arboreal. But these days, when you ask a kid to climb a tree, there's a pause while the child tries to figure out a tactful way to point out that people don't do that anymore. It's like you've asked the kid to churn butter or boil up a vat of lye.

At some point you'll deliver the entire canned speech about how, as a child, you were always building forts, exploring forest trails, roasting squirrels over a fire, and so on, the classic Huck Finn sort of existence, and the only thing you'll forget to mention is that you were nearly fatally bored.

Face it, we had no choice but to play in the woods, because civilization hadn't yet invented Nintendo. Kids today don't know the crippling intensity of stupefaction that afflicted young people before the coming of personal computers and MTV.

CDBG lives.

This is news to be cheered, though I can’t resist using it to point out for the trillionth time how truly pathetic the modern GOP has become on these budget issues, from a small-government conservative's perspective. Discretionary spending on poverty is supposed to be the first casualty of any garden-variety starve-the-beast gambit, and on the margins one could say that this has been the case in the past few years. But if a unified Republican government running enormous deficits can’t manage to make even a dent in a program targeted at impoverished neighborhoods and their predominantly Democratic municipal governments, exactly how seriously should we take that party’s supposed governing philosophy?Two questions:

(1) Mark Schmitt has described the budgeteering trick of pretending to cut a popular program that you know Congress will restore, allowing the administration to claim credit for trying to ax it and Congress to claim credit for saving it. Is this what happened here?

(2) I have seen data suggesting that the Republican Congress has shifted the balance of federal spending towards GOP congressional districts, far out of proportion to the minor imbalance favoring Democrats before 1994 (sorry, no link just now). It wouldn't surprise me if CDBG grants now go disproportionately to GOP areas, creating a constituency to save them (see (1) above). Anyone know if that's true.

Remember, these Republicans are not about cutting government -- they're about looting the government for their own. Accusing them of hypocrisy on the "cutting government" thing is getting old. Who cares about any hypocrisy, or taking their philosophy seriously? Stick to pointing out that they're all about looting the government.

Subscribe to Posts [Atom]