Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Faux news.

Fox dispatched a reporter to an ESPN Zone in Washington, DC, where they were lucky to find "online shopper" Peter Perweiler, who did indeed have big online shopping plans. "I'm looking at some big-ticket items this year," he said, "so I really want to know what other people - problems they're having with items, things of that nature."Silicon Alley Insider.

Good to know. What would also have been good to know: Peter is also the marketing manager at the National Retail Federation.

A prurient interest.

Monday, November 26, 2007

How did Tom Friedman miss this?

It's a terrific story by the New York Times, in its conception and execution, and the pictures are not to be missed. One quibble, though, is that the map included with the story points to Dhaka, Bangladesh, which is the next country over.At Shakti, street grates, manhole covers and other castings were scattered across the dusty yard. Inside, men wearing sandals and shorts carried coke and iron ore piled high in baskets on their heads up stairs to the furnace feeding room.

On the ground floor, other men, often shoeless and stripped to the waist, waited with giant ladles, ready to catch the molten metal that came pouring out of the furnace. A few women were working, but most of the heavy lifting appeared to be left to the men.

The temperature outside the factory yard was more than 100 degrees on a September visit. Several feet from where the metal was being poured, the area felt like an oven, and the workers were slick with sweat.

Often, sparks flew from pots of the molten metal. In one instance they ignited a worker’s lungi, a skirtlike cloth wrap that is common men’s wear in India. He quickly, reflexively, doused the flames by rubbing the burning part of the cloth against the rest of it with his hand, then continued to cart the metal to a nearby mold.

Once the metal solidified and cooled, workers removed the manhole cover casting from the mold and then, in the last step in the production process, ground and polished the rough edges. Finally, the men stacked the covers and bolted them together for shipping.

“We can’t maintain the luxury of Europe and the United States, with all the boots and all that,” said Sunil Modi, director of Shakti Industries. He said, however, that the foundry never had accidents. He was concerned about the attention, afraid that contracts would be pulled and jobs lost.

Sunday, November 25, 2007

Foxy.

More and more foxes are seeking their fortunes in German towns, where food is ample and people sometimes mistake them for overgrown dachshunds. . . .Der Spiegel. Unfortunately, the foxes bring increased risk of tapeworm.

One particular fox couple in the village of Grünwald south of Munich ("Felix" and his girlfriend "Speedy") waits for the proper signal to cross the street along with the pedestrians, he said. On one occasion König observed them at rush hour crossing a busy thoroughfare along with the work crowd. "No one noticed them," König says.

But I don't know these CSS fellows.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

It's the shipping that gets you.

If anyone knows how I can get my hands on a copy of Alexis Wright's Carpentaria without paying $30 (AUD) to have it shipped DHL, do let me know in the comments. I looked into this months ago, to the same result.

Friday, November 23, 2007

Struck an iceberg.

154 people escaped the wreck of a cruise ship, the Explorer, which struck an iceberg off Antartica, south of Chile.

Judge the covers, not the books.

Adventures in modern whaling.

In Vava'u [Tonga], the local people tried strapping half-sticks of dynamite to the harpoon shaft. The practice required very careful timing. The fuse for the dynamite had to be cut to the right length and lit just before throwing the harpoon. The technique was abandoned after one harpooner threw the charged harpoon into the whale, the whale dived, and the while line tugged out the harpoon. It floated up, right under the boat, and exploded, destroying the whaleboat. The crew escaped without loss of life but they had been hoisted, quite literally, by their own petard.Tim Severin, In Search Of Moby Dick 113 (Little, Brown & Co., 1999).

Thursday, November 22, 2007

Thursday, November 9, 1620.

. . . Jones tacked the Mayflower and stood in for shore. After an hour or so, all agreed that this was indeed Cape Cod.Nathaniel Philbrick, Mayflower 35-39 (Penguin, 2006).

Now they had a decision to make. Where should they go? They were well to the north of their intended destination near the mouth of the Hudson River. And yet there were reasons to consider the region around Cape Cod as a possible settlement site. In the final chaotic months before their departure from England, Weston and others had begun to insist that a more northern site in New England . . . was a better place to settle. . . . But when the Mayflower had departed from England, it had been impossible to secure a patent for this region, since what came to be called the Council for New England had not yet been established by the king. If they were to settle where they had legally been granted land, they must sail south for the mouth of the Hudson River 220 miles away.

Master Jones had his own problems to consider. Given the poor health of his passengers and crew, his first priority was to get these people ashore as quickly as possible -- regardless of what their patent dictated. If the wind had been out of the south, he could easily have sailed north to the tip of Cape Cod to what is known today as Provincetown Harbor. With a decent southerly breeze and a little help from the tide, they'd be there in a matter of hours. But the wind was from the north. Their only option was to run with it to the Hudson River. If the wind held, they'd be there in a couple of days. So Jones headed south.

Unfortunately, there was no reliable English chart of the waters between Cape Cod and the Hudson. . . . Except for what knowledge his pilots may have of this coast -- which appears to have been minimal -- Jones was sailing blind. . . .

For the next five hours, the Mayflower slipped easily along. After sixty-five days of headwinds and storms, it must have been a wonderful respite for the passengers, who crowded the chilly, sun-drenched deck to drink in their first view of the New World. But for Master Jones, it was the beginning of the most tension-filled portion of the passage. Any captain would rather have hazarded the fiercest North Atlantic gale than risk the uncharted perils of an unknown coast. Until the Mayflower was quietly at anchor, Jones would get little sleep. . . .

They sailed south on an easy reach, with the sandy shore of Cape Cod within sight, past the future locations of Wellfleet, Eastham, Orleans, and Chatham. Throughout the morning, the tide was in their favor, but around 1 p.m., it began to flow against them. Then the depth of the water dropped alarmingly, as did the wind. Suddenly, the Mayflower was in the midst of what has been called "one of the meanest stretches of shoal water on the American coast": Pollack Rip.

Pollack Rip is part of an intricate and ever-changing maze of shoals and sandbars stretching between the elbow of Cape Cod and the tip of Nantucket Island, fifteen or so miles to the south. The huge volume of water that moves back and forth between the ocean to the east and Nantucket Sound to the west rushes and swirls amid these shoals with a ferocity that is still, almost four hundred years later, terrifying to behold. It's been claimed that half the wrecks along the entire Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States have occurred in this area. In 1606, the French explorer Samuel Champlain attempted to navigate these waters in a small pinnace. This was Champlain's second visit to the Cape, and even though he took every precaution, his vessel fetched up on a shoal and was almost pounded to pieces before he somehow managed to float her free and sail into Nantucket Sound. Champlain's pinnace drew four feet; the deeply laden Mayflower drew twelve.

The placid heave of the sea had been transformed into a churning maelstrom as the outflowing tide cascaded over the shoals ahead. And with the wind dying to almost nothing, Jones had no way to extricate his ship from the danger, especially since what breeze remained was from the north, pinning the Mayflower against the rip. "[T]hey fell amongst dangerous shoals and roaring breakers," Bradford wrote, "and they were so far entangled therewith as they conceived themselves in great danger." It was approaching 3 p.m., with only another hour and a half of daylight left. If Jones hadn't done it already, he undoubtedly prepared an anchor for lowering -- ordering sailors to extract the hemp cable from below and to begin carefully coiling, or flaking, the thick rope on the forecastle head. If the wind completely deserted them, they might be forced to spend the night at the edge of the breakers. But anchoring beside Pollack Rip is never a good idea. If the ocean swell should rise or a storm should kick up from the north, any vessel anchored there would be driven fatally onto the shoals. . . .

Just when it seemed they might never extricate themselves from the shoals, the wind began to change, gradually shifting in a clockwise direction to the south. This, combined with a fair tide, was all Master Jones needed. By sunset at 4:35 p.m., the Mayflower was well to the northwest of Pollack Rip.

With the wind building from the south, Jones made a historic decision. They weren't going to the Hudson River. They were going back around Cape Cod to New England.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Betting on horses.

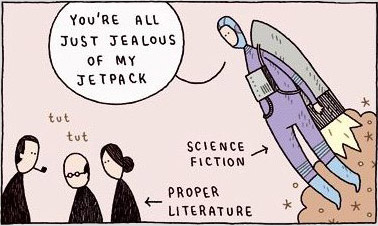

Jealous of my jetpack.

Bon voyage!

Wise counsel.

Putt-putt.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Underpromise your way to success.

Airline executives should rush to the Haunted Mansion in the Magic Kingdom. Our heads sank when we approached and saw the sign advertising a 15-minute wait. Despair turned to elation when we were ushered into the spooky entry hall in just a few minutes. This experience was repeated time and again—at rides and restaurants—where promised delays of 20 minutes miraculously shrank in half. After a few days, it became apparent that this might be a conscious strategy of underpromising and overdelivering. Which is precisely the opposite of the tack airlines have taken lo these many years. The carriers continually promise that planes will leave or arrive at a specific time when they know the probability of an on-time departure is only slightly greater than the probability of your suitcase's being the first item to hit the luggage carousel.Daniel Gross.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Found on Ffffound.

Saturday, November 03, 2007

Urban eden.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]