Friday, June 29, 2007

Nature builds structure algorithmically.

David Owen describes the creation of a temporary pavilion commissioned by the Serpentine Gallery for Kensington Garden, designed by architect Toyo Ito and engineer Cecil Balmond:

Ito had said that he wanted to build "a box that is not a box," and he proposed a rectangular building that would have an orderly colonnade around the perimeter but roof beams positioned randomly, as though scattered from above. Balmond disapproved. "It just didn't look right," he said last fall, in a well-attended lecture at Cooper Union, in New York. "It looked precious, in a way."David Owen, "The Anti-Gravity Men," The New Yorker 76-77 (June 25, 2007) (not available on-line, though an abstract is).

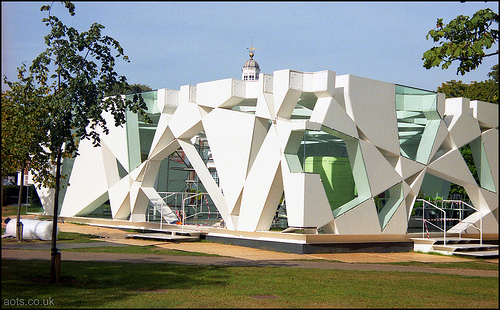

The pavilion as it was built was a typically Balmondesque transformation of the architect's original concept. Balmond began by drawing a square. Then he superimposed a second square, somewhat smaller and turned slightly askew, and then a third square, and so on, until he had filled the sheet. Then he extended all the lines until they reached the edges of his sketchbook. When he finished, the page looked like a pane of glass fractured into asymmetrical trangles and other polygons, but the underlying pattern was actually regular: a spiralled square. For the pavilion, Balmond and Ito folded the pattern to form a box, turned the lines into steel plates, and filled in roughly half of the polygonal openings with panels. The interior looked a little like a three-dimensional projection from a broken kaleidoscope -- a box that, to people sitting at café tables inside it, didn't appear to be a box. The building was described by the Financial Times as "one of the most beautiful and delicate structures seen in London in recent years" . . . .

For Balmond, the Ito Serpentine pavilion was a telling example of what he calls the power of algorithm, of a simple mathematical rule repeatedly applied. Nature builds structure algorithmically -- one call becomes two, two become four, four become eight -- and Balmond allowed the pavilion's design to generate itself in an analogous way. . . . A member of the A.G.U. who worked on the pavilion told me that the load path created by the algorithm had serendipitously turned out to be just as efficient as a traditional grid: despite its apparent complexity, the pavilion stood up by itself and was easy to construct. During assembly, a workman, using wooden blocks, propped up one of the corners, which looked precarious to him because it didn't touch the ground -- entirely unnecessarily, as Balmond was able to show him by kicking away one of the blocks.

Owen's article cries out for more pictures, but The New Yorker is not That Kind Of Magazine. The interwebs come to the rescue, here and here. If you want to read more about Cecil Balmond but can't find the June 25 New Yorker, here's a 2003 article by Justin McGuirk in the Guardian (UK)., in which McGuirk suggests Balmond is "a brilliant, mad, mystic pervert," or at least perceived as such by the world's leading architects. Balmond's novel Number 9: The Search for the Sigma Code will cost you $129.43 on Amazon.

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]